Hannah Perry’s exhibition on Baltic’s level 4 offers a very different experience to the one it has replaced, Michael Rakowitz’s display of greenery with its garden centre planters under natural light.

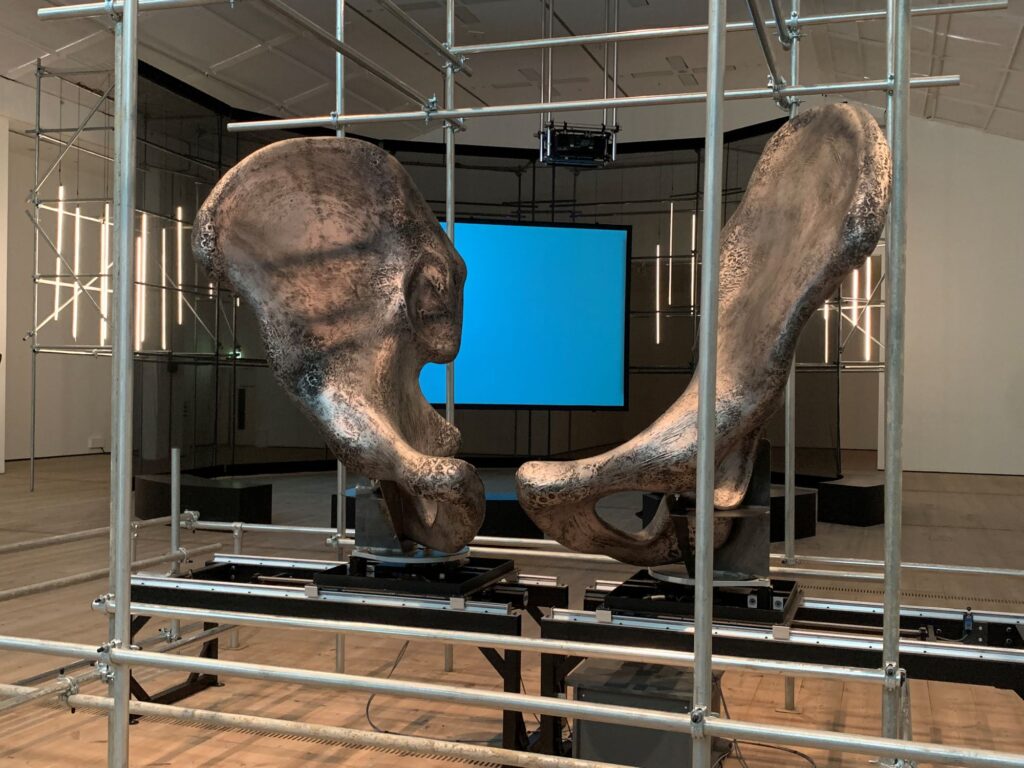

Machine-like structures and neon strips are there now, the latter framing a giant screen and flashing in accordance with the computer programme that governs everything you see and hear.

But what might have greeted visitors if the exhibition had gone ahead as originally intended in 2020?

Would it have featured the outsize pelvis which mechanically separates to resemble mighty antlers?

- Read more: Second serve for tennis trailblazer

- Read more: A Grand day out at Beamish

Overseeing the final touches, Hannah takes a moment to reflect on the tumultuous years since Baltic first came calling, alerted to the interesting work being done by a London-based Northern artist drawn to heavy materials and matters relating to class and gender.

In 2020, she recalls, she had been absorbed in a body of research arising out of a trip to Russia the previous year — a fact that sounds extraordinary in light of what has happened subsequently.

There had, of course, been no inkling of an invasion of Ukraine in 2019, despite the annexing of the Crimean peninsula five years previously.

Hannah was invited to take part in the Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art in the city of Yekaterinburg, situated in an area of heavy industry.

“It’s designed to connect people with the local industry and I’m assuming I was selected because I use industrial materials such as steel and concrete,” she tells me.

“At the time I was looking particularly at male-dominated workspaces so we went to the biggest titanium factory in the world.

“I also asked to film at a mine so they took me to Asbest (the site, as you might have guessed, of a mighty asbestos mine).

“When I said I wasn’t sure how comfortable I was to be filming there, they let me use drones.”

- Read more: Royal promotion for Gerry and Sewell

- Read more: Everyone should vote for change

Russia, she tells me, was “different”.

While the organisers of the biennial were open-minded and friendly, they were also wary, happy to direct the Dutch members of an LGBT art collective to an underground drag club but unwilling to accompany them.

Then there were the schoolchildren at the Boris Yeltsin Museum, one of whom rushed forward to kiss a photo of Vladimir Putin.

None of this is in the film but there is footage of white-hot metal rods being pounded, sparks flying, and of the dust clouds released by controlled explosions in the asbestos mine.

It is, as Hannah says, “very violent, tough and aggressive”.

But then Covid happened and the Baltic show got postponed until 2022. “And in the meantime I had two kids which completely changed the course of everything!” says Hannah.

She laughs at the way events have unfolded.

Becoming a mother is part of the exhibition which it wouldn’t have been in 2020. Although she was pregnant when she accepted the Baltic commission, the experience had yet to feed into her artistic practice.

Juxtaposed with the Russian film is footage of herself, heavily pregnant in the hall of mirrors she constructed in her studio to give multiple images, first alone and then dandling her daughter on her naked ‘bump’.

The little girl was born (by caesarean section) in 2020, her baby brother in 2022.

The title of the 17-minute film, Manual Labour, references the muscular factory footage and the internal ‘bodily violence’ of childbirth — and also the process of transition, of raw material into industrial product and of woman into mother.

It’s a process, she says, of going from a singular to a non-singular entity, of caring just for yourself and then instinctively for another. “You go through these physical and emotional changes. It’s a sort of rites-of-passage transition.”

Hannah’s experience of giving birth as a first-time mum during Covid sounds far from ideal, denied the support of her partner once the baby had been delivered and the joyous moments with family. The hospital staff, she says, were visibly stretched to the limit.

At some point she was also diagnosed with gestational diabetes which doesn’t sound nice at all.

“It was a very strange time,” she says with cheerful understatement.

“We were living back then in a small London flat with no outdoor space and because of the diabetes I was high risk, so even going for a walk was problematic.”

Probably all expectant first-time mothers become acutely aware of the mechanics of childbirth and its sheer unfeasibility.

But as an artist with an interest in how things work, Hannah set out to demonstrate the properties of the female pelvis and how, with the help of a naturally produced hormone called relaxin, its connecting tissues loosen to make possible the seemingly impossible.

Her giant pelvic sculpture, which she called Antagonist, periodically comes apart on level 4 with a slow-motion jitter.

“It’s not as violent as I initially anticipated it to be,” she confesses. “Maybe the scale is imposing enough.”

It looks like metal and would have been metal if weight hadn’t been an issue. Instead it’s made of resin and was constructed to Hannah’s specifications by a renowned firm of London prop-makers.

The exhibition, with all its elements co-ordinated, also comprises a sound piece, called Chorus, with a female voice emanating from speakers positioned around the gallery, and a double-sided audio-visual work.

On one side of this is a triptych of paintings and a screenprint from the artist’s Factory Floor Series (engine oil listed as a material along with bronze powder and paint) and on the other is what she accurately describes as ‘a mirrored kind of metal wobbly sculpture thing’.

Occasionally it oscillates. Frequently people are going to be photographing their hazy reflections.

Hannah, who was born in Chester, is in some respects an unlikely artist. There have been obstacles to overcome.

She’s dyslexic, for one thing. And she says she got little encouragement at school or even afterwards during her foundation year, being told there was no point in her applying to the renowned Goldsmiths, University of London, because she simply wouldn’t get in.

She got in, graduated with a BA in Fine Art in 2009 and subsequently acquired an MA from the Royal Academy of Arts.

Perhaps she was used to people dampening her ambitions. She remembers, aged about 14, saying to her father, a welder, “I want to learn how to weld”, and being told it wasn’t ladylike.

Her brother wasn’t discouraged from becoming a professional welder but Hannah had the last laugh, having made strides in her chosen field of art.

She welds, bashes metal, ventures into testosterone-infused workplaces and in doing so shows that ‘ladylike’ can be whatever a lady chooses it to be. Often, she says, her dad has helped in the making of her sculptural pieces — under her supervision, of course.

Through her work, she professes to give a voice to young working-class women and mothers who do not, she tells me, always get fairly portrayed in the media.

Having passed through doors that threatened to remain firmly closed, she is well placed to be a trailblazer, particularly with this exhibition at Baltic.

“It’s a big deal for me, this show, quite a step-change,” she says. “I was delighted to be given the opportunity.”

Hannah Perry: Manual Labour runs until March 16, 2025. Details of opening hours are on the Baltic website