It’s Beamish, the denizens of the Living Museum of the North are in period costume and in the projection room of The Grand, Bill Mather is remembering the day he got his long trousers.

Bill isn’t in period costume. He has come as himself to renew acquaintance with the place he calls “my palace of dreams”.

Never lost for words, he can be forgiven for feeling a little in awe. “Like walking into a dream,” he says.

- Read more: Second serve for tennis trailblazer

- Read more: Royal promotion for Gerry and Sewell

When he first encountered the building it was in Ryhope, near Sunderland, and known as the Grand Electric Picture House. Since 1912 it had been a magnet for local people, no doubt kindling many a romance.

Bill’s love affair with cinema certainly started here.

“I was born for this place,” he says. “That’s what my mam used to say. We only lived a few hundred yards away.”

At the age of eight he would be making himself useful to the chief projectionist, Jack Thompson, passing things up to him as he was installing promotional material for forthcoming attractions.

Jack knew everything about the cinema. Having joined when it opened, he made it his life’s work, staying for 45 years. Bill hung on his every word and at the age of 10 asked if he could be admitted to the projection room during a night-time screening.

Bill remembers his response as if it had been uttered yesterday.

“He said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I will let you in but I’ve got one problem. If someone in authority sees you in short trousers, we’ll get into trouble. Do you think your mam will buy you a pair of long trousers, son?’ He always called me son.

- Read more: New city art venue showcasing local talent

- Read more: Howzat for an eye-watering experience

“My mam did get me a pair and I’ll never forget when I climbed up into the projection room, Jack started clapping. He said, ‘You’re all right now, son’.”

Bill was in his element — and clearly, at the age of 83, remains so.

“I still remember the film,” he says. “It was The Jolson Story with Larry Parks. That was the first time I was allowed in. It was a Friday night.”

Jack Thompson’s long gone and it’s a minor miracle that The Grand hasn’t gone too. Many cinemas of this and even later eras, and many that would have made The Grand seem rather humble, have been reduced to rubble.

But the little cinema in Ryhope, being of the right type and period, was handed an unlikely reprieve, having spent years as a bingo hall and then as an unconventional garage for a collection of cars.

Taken down brick by brick, it has been carefully reconstructed on Front Street, Beamish, at the heart of the museum’s 1950s Town.

Bill left school and joined the staff of a cinema in Sunderland and then moved to Dawdon, County Durham. Eventually he got into management, running cinema chains in Scotland and the North East.

But this place harbours his fondest memories. It was here in 1952 that he was given permission to start the main evening feature as Jack went down to draw back the curtains from the screen. Everything was manual back then.

The film, he remembers, was Ruby Gentry with Jennifer Jones and a young Charlton Heston. It was in black and white.

It was also where he learned to edit. With two showings nightly, there was always the danger that the final credits wouldn’t roll in time for the last bus from Ryhope to Silksworth, leaving customers stranded.

“This particular night, Jack said to me, ‘Look, son, we’re going to have to get 10 minutes out of the second feature. Now watch how it’s done’.

“It was Rio Grande, a Western directed by John Ford with two or three Indian battles. Jack said, ‘We don’t need that one’, so he spliced it out of the film, joined the ends and put it on screen with one battle chopped out.

“Occasionally you’d get customers asking how come the first house lasted two hours and a quarter and the second only two. Jack always had a plausible answer. Anyway, by the time I was 14 or 15, I knew how to edit.”

Having been given the thumbs up by Bill, visitors can take it that this was just as The Grand was in its heyday — even if the projectors, demonstrated by Dan Hudachek, Beamish’s head of collections, came from a lecture theatre at Durham University and the seats from the old Palladium, in Durham, which is now student accommodation.

The Grand will throw open its doors to Beamish visitors on July 6, offering a rolling programme of short films, along with its new 1950s neighbours, a toy shop named after the Romer Parrish establishment in Middlesbrough and an electrical store named after Alan Reece, founder of the Reece Foundation which has funded a learning space at Beamish.

Many a memory will be stirred here.

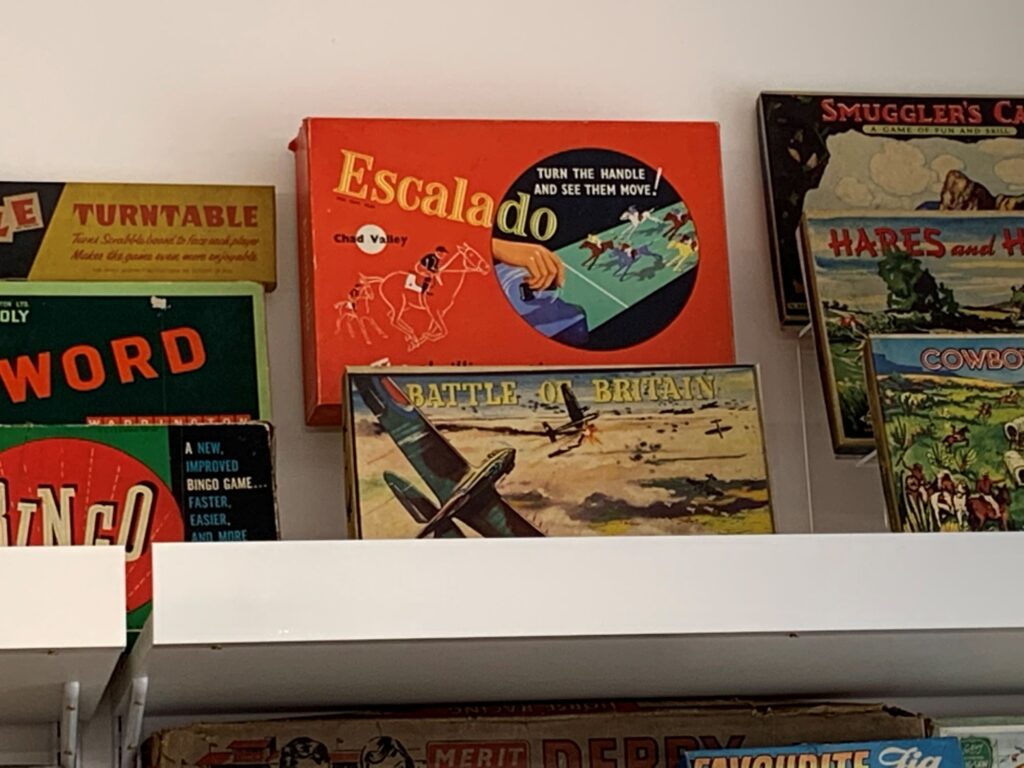

For me, the catalyst is the Escalado racing game which we played as a family when I was growing up. I still have it, though rather more battered than this example from Beamish’s fantastically well-stocked stores.

Is there anything more indicative of the march of time than seeing a childhood plaything become a museum exhibit? Er, no. Let’s move on.

Shop assistants Rachael Marsden and Elisabeth Walls are in charge today of the dolls’ hospital section of the shop where plenty of frankly scary-looking plastic specimens await treatment for some serious ailments, including limb replacement.

Some items here are for sale, others for display only. But it can be hard to tell the difference. Elisabeth shows me a mint-condition 1960s version of Beetle Drive and its modern equivalent. Whoever invented that was onto a winner.

Open already is The Drovers Tavern, the new hostelry near Pockerley Old Hall. Dating from the 1820s, it seems they couldn’t find anyone who actually worked there all those years ago.

But Beamish staff are cheerfully doing what Beamish staff do, bringing the past to life in costumes that, while accurate in just about every respect, are possibly a little less grubby than those worn hereabouts in the early 19th century.

Seb Littlewood, senior keeper of Georgian and farm life (which has to be one of the most covetable of 21st-Century job titles), explains that pubs didn’t exist back then. It was all taverns, inns and alehouses with subtle distinctions between them.

Drovers, of which Ed Lawrenson cuts a fine example, were part of country life for generations, driving sheep and cattle vast distances to market and no doubt working up a ferocious thirst in the process.

Inside, in the rustic shade, Kelly Sephton, Beamish’s food team leader, displays the summer fare of The Drovers Tavern, prompting wistful thoughts of hostelries of yesteryear.

In short, there’s lots to see at Beamish this summer that’s new. And, of course, old.

Details of opening times and admission can be found on the website of Beamish: The Living Museum of the North