One morning lately we boarded a London train (‘Daytripper yeah…’) and were advised over the PA to get our tickets ready for inspection.

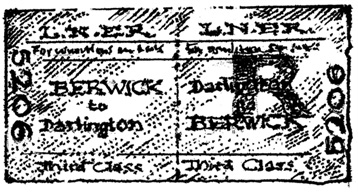

This sometime pedant knew this was impossible. We should have been asked to produce our mobiles and find an image on a screen. There was no ticket, no ‘it’— and I wondered what Thomas Edmondson would have made of that?

In 1836, after the failure of his cabinet-making business Thomas became stationmaster at Brampton on the Newcastle-Carlisle line. Business was brisk, so he was kept busy task writing tickets for his customers by hand. You can almost hear the scraping of nib on paper, the tapping of boots on floorboards and the muttering of travellers as they watched their train leave without them. Imbued with the resourceful spirit of his age, Thomas knew there must be a better way and set out to prove it.

Between arrivals and departures he used his woodworker’s tools to fashion a small printing press to run off strips of cardboard tickets with the help of a sharp blow with a mallet but didn’t stop there. He made a device in which tickets of the same class and destination could be shifted upward in numerical order every time a ticket was extracted from the top.

Little wonder a railway historian has described the North East as the Silicon Valley of its day. This truth is recognised around the world.

Finally, with the help of a Carlisle clockmaker, he developed a contraption housing iron jaws set with movable type and inked ribbon which printed the day of issue on each ticket. The invention— a complete system for printing, storing and issuing — was brilliant, but his superiors in Newcastle weren’t impressed. Undaunted, Thomas made a deal with the Manchester and Leeds Railway, the first of many others.

It’s a measure of the success of Thomas’ invention that in 1933 the ticket stock of the London Midland Railway alone amounted to 300 million, comprising 90,000 different types.

A few years later the printing works of the Southern Railway printed 450,000 tickets every day — the same size (two and a quarter by one and three-sixteenth inches) as ones issued by Thomas at Brampton Station in the late 1830’s. The last Edmundson ticket was issued in1990.

He did quite well then, the Edmundson lad, a small part of the great industrial and social revolution brought about by the development of railways in the first half of the 19th century — and the key role played in it by the North East.

I learnt this lesson early in life.

One day I was taken by my father from my grandparents’ pit house in Ferryhill to the side of a railway nearby. A wooden fence stood between us and a dozen separate tracks with rows of goods wagons on the far side. We waited. Then Dad tapped my shoulder and pointed south to a distant plume of smoke.

‘See? It’s coming.’

Before I knew it the train was upon us with the roaring of moving parts and the maniacal shriek of its whistle. We were enveloped in a squall of hurricane proportions. I lost my hat and it seemed my wits. Then it was gone and Dad and I began to laugh. He pointed out that the wagons were full of coal produced by Ferryhill’s two pits — Mainsforth and Dean & Chapter —where various menfolk in my family, including him, had laboured down the decades.

- Read more: Looking for Tyne

- Read more: The most important 21 miles in the region

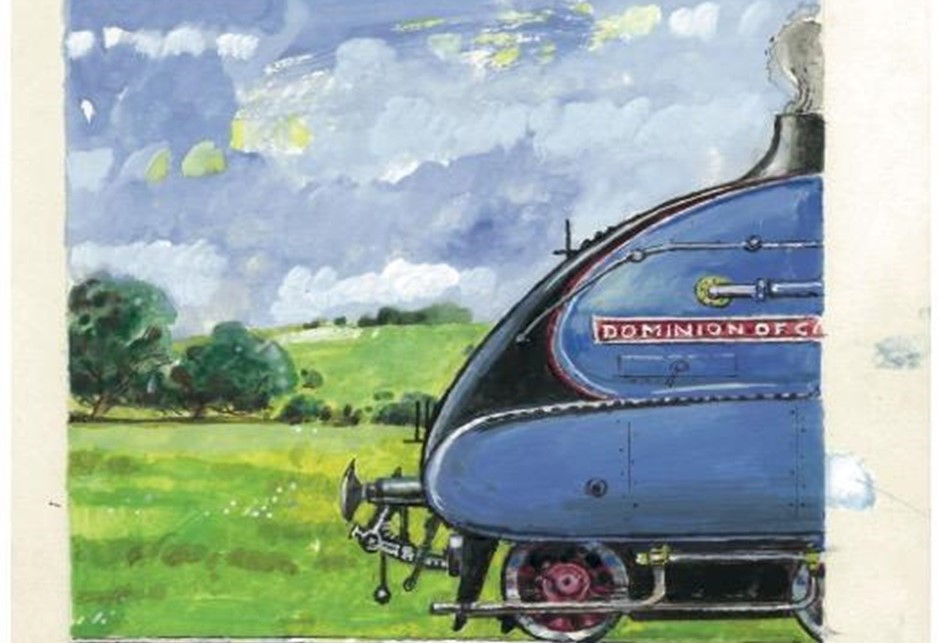

But what stayed in my mind was the beauty of that mighty engine with a sloping front, which I now know was named Mallard and holder of a never-surpassed speed record.

There’s an almost overwhelming temptation to write nostalgically about railways, especially those of the steam age, but there’s far more to them than sentiment. They opened up the world in an unprecedented way, turning the Industrial Revolution into a social revolution that transformed many other countries —and it all started by the Tyne.

Railways began as waggon ways to transport coal to the ships taking it to market, with the horse as motive power. There were nine on Tyneside by 1660 and they were so synonymous with the northern coalfield they came to be known as ‘Newcastle roads’.

The birth of steam-driven railways represented a huge leap forward and being as they are an amalgam of separate components — engine, track, rolling stock, which all required gradual development— they had many midwives. But the cleverest hands belonged to George Stephenson, obstreperous, self-educated genius of Tyneside. He had a brilliant knack of developing other people’s ideas, shaking them till they worked and overcoming every obstacle, from exploding boilers to lawyers who mocked his accent.

Two members of my own family shared the skills that George Stephenson nurtured: the ability to take apart and put back together just about any working mechanism. It seems such skills are no longer valued in our culture.

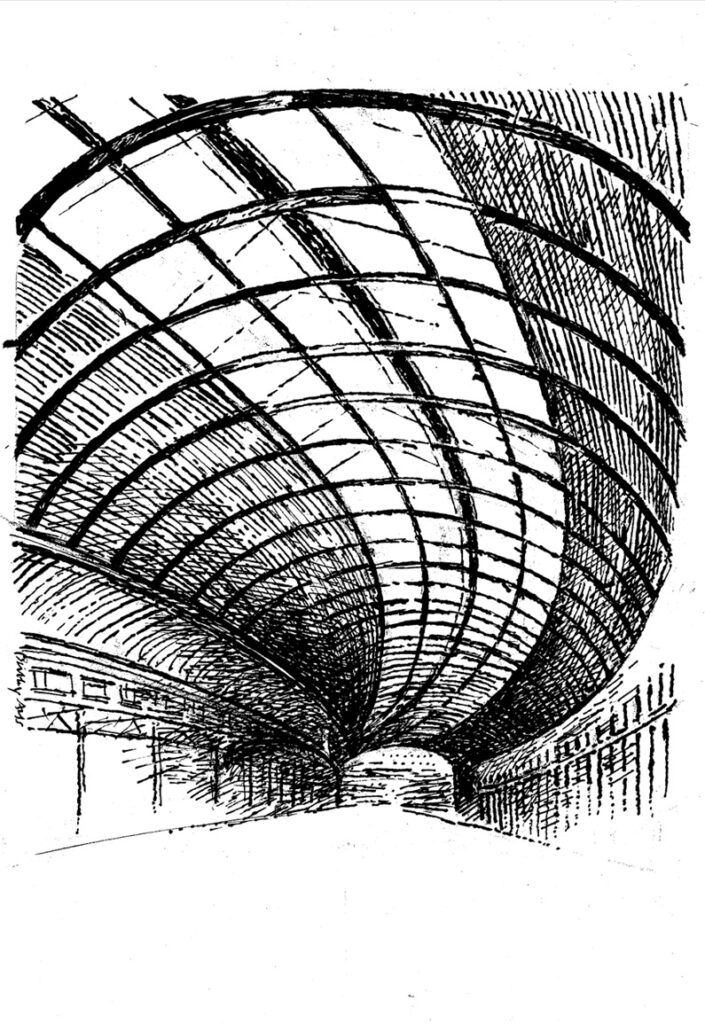

The heart of his world-changing enterprise was Forth Banks works, just by his son Robert’s Central Station. There in the 1820’s Locomotion was built for the Stockton and Darlington Railway and Rocket for the Liverpool and Manchester. By 1850 the railways had penetrated every corner of the British Isles. Many of the resulting breakthroughs were made by father, son and their men.

Little wonder a railway historian has described the North East as the Silicon Valley of its day. This truth is recognised around the world. Example: the Chaplins were once exploring Budapest when we came across its vast Keleti Station and noticed two statues in pride of place: inspirational figures without whom it wouldn’t have existed: James Watt and our own Geordie Stephenson.

Of the many effects of this transport revolution perhaps the greatest was on the lives of the common people. Before railways came along, horse-drawn coaches were so expensive that the masses hardly moved at all and when they had to, they walked. Thomas Bewick, wood-engraver of this parish, once decided to visit friends in the Lake District and so walked there, then felt the urge to see Scotland and promptly strolled off to Edinburgh.

Trains changed all that. Cheap Third class tickets ensured that industrial workers could enjoy, among many benefits, family excursions to the seaside and fresh fish however far inland they lived. From the beginning railways were the most democratic of transports, a shared experience for all.

My first experience of rail travel was in 1953, when I was two. The whole family — Mam Rene and Dad Sid, sister Gillian and brother Chris — embarked on the six-hour journey from Ferryhill’s little station to the grand terminal of King’s Cross.

The train had no connecting aisle, being divided into separate compartments. At York, dad jumped off to buy a newspaper and cigarettes but didn’t reappear before the train pulled out, to the growing anxiety of my mother. Sid had tickets, money and knowledge of how to travel on to our new home in Essex. At King’s Cross Rene walked along the platform with her fractious children, rehearsing a speech to the ticket collector. Then she saw her husband leaning against some railings with an insouciant smile. Family legend suggests he didn’t wear it for long…

Almost every house I’ve occupied in almost 70 years has been by a railway. Indeed my life has been more or less defined by one, the East Coast mainline.

I once heard a black and white shirted football fan debate Karl Marx with a Civil Service mandarin working a piece of embroidery

It’s true I lived for a while beside the track carrying electric trains between Liverpool Street and Southend and another 15 overlooking a stretch of London’s District Line near its Wimbledon terminus. It was hard to get excited about these prosaic branches of the railway family, though from my study window in Southfields I enjoyed watching another kind of commuter on the track — foxes loping towards town in the morning and back again in the afternoon.

No, from childhood it was always the London to Edinburgh route that, well, floated my boat. As a boy lying in bed in Jesmond Vale the whuff-whuff of steam locos crossing Byker Bridge often lulled me to sleep. Forty years later I found myself living at the destination of many of those trains, in Edinburgh.

In summer I would open my study window and hear a lilting female voice from nearby Haymarket, announcing imminent departures for points north. My favourite was for the Fife Circle line, ‘calling at Dalmeny, North Queensberry, Inverkeithing, Dalgety Bay, Aberdour, Burntisland, Kinghorn, Kirkcaldy, Glenrothes, Cardenden, Lochgelly, Cowdenbeath, Dunfermline Town, Rosyth, Inverkeithing, North Queensferry and Dalmeny…’

This euphonious poem of place got so under my skin I eventually wrote a radio play inspired by it, in which two old men — train driver and High Court judge— rattle around the Kingdom of Fife and discover they are half-brothers. Both parts were played by that master of disguise Stanley Baxter, who himself did much travelling between Scotland and London, though coming from Glasgow he travelled on the West Coast route, poor man.

Illustration by Birtley Aris

Living once more in Newcastle, I take the London train maybe once a month. I couldn’t begin to count the number of trips I’ve made on this line over the years — hundreds — but I do know that if I was somehow teleported onto a train in mid-journey, it would only take a few minutes before the topography told me where I was.

In my London years, I came north for family parties, holidays by the sea, play rehearsals at Live Theatre, countless Newcastle matches and the occasional funeral. When my father died, the train crawled north, the rattle of the wheels a song of grief. But usually the journey’s a transport of delight.

One looks at the landscape through a rectangular frame and the sense of cinema is enhanced when the traveller considers that one is as powerless to intervene in what one sees as James Stewart in Rear Window. This constantly changing panorama reminds the viewer that England remains a green and pleasant land, but as the miles click off, everything gets grander.

Leaving London, we pass over Hertfordshire’s oddly named River Mimram, via two sluggish Ouses, a Trent with several channels and a blackened Don to the holy trinity of Tees, Wear and Tyne. It’s the same with the progression of cathedrals: the minsters of Doncaster and York are an improvement on Peterborough but suffer by comparison with the matchless grandeur of Durham’s perched on its rock. And finally to Newcastle…

Almost every house I’ve occupied in almost 70 years has been by a railway. Indeed my life has been more or less defined by one, the East Coast mainline.

To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive, said Robert Louis Stevenson, who crossed America by train in 1879. Perhaps he was thinking of his destination, Los Angeles (of which Gertrude Stein famously remarked, ‘There is no there there), a dirge-like hymn to the motor-car.

One couldn’t accuse the great gorge of the Tyne with its dizzy procession of bridges of such emptiness, though Queen Victoria might not have agreed. She travelled north in 1850 to open our great station but was apparently sent a hotel bill by the city fathers her stay. Forever afterwards, en route to Balmoral and back, she lowered the blinds as the royal train passed through the smoky city that had so grievously insulted her.

On my London journeys, I sometimes reflect on the contribution of railways to our culture.

Think of the books: everything from Graham Greene’s Stamboul Train and Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express to Dickens’ Dombey and Son, the complete works of WH Awdry and Trollope’s Barchester Chronicles, which aren’t about trains but were mostly written on them. In poetry we’ve Larkin’s Whitsun Weddings, more Betjeman than you could wave a green flag at and that most evocative of opening lines: I remember Adlestrop…

In music, there’s Chattanooga Choo-Choo and Last Train to San Fernando, as well as the heavyweight majesty of Honegger’s Pacific 231 and Steve Reich’s haunting Different Trains, as well Paul Simon’s beautiful song Homeward Bound, written one morning in 1965 at Widnes Station as he waited for a train to take him back to his London girlfriend.

In film there’s a long list of movies that present the rich diversity of human experience, beginning with the prosaic Arrival Of A Train of 1897; war films like The Train and Von Ryan’s Express; thrillers like From Russia With Love and The Taking of Pelham 123, and Hitchcock’s trio of The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes and Strangers On A Train; comedies like Buster Keaton’s The General and Ealing Studios’ The Titfield Thunderbolt; and the, well, sheer poetry of Auden’s Night Mail.

Movies about the culture of the motor-car are rather bleaker: Thelma and Louise doesn’t end well, nor Spielberg’s reputation-making Duel. Often the car is seen as a signifier for the dystopian hell of modern life.

In real life there’s nothing on trains to match the nihilistic aggression of road-rage, apart from occasional disagreements about mobile phones. In my experience people usually behave like civilised beings and the vignettes on view are colourful. I once heard a black and white shirted football fan debate Karl Marx with a Civil Service mandarin working a piece of embroidery, a train guard recite Spike Milligan poems and a hilariously inebriated Scotsman serenade his carriage with songs from the shows.

The essential point is that politicians consistently miss the point: railways aren’t the transport system of the past but the future. Hardly surprising: these people usually travel in ministerial limos — or helicopters in Rishi Sunak’s case.

Perhaps a railway carriage is what anthropologists call a ‘liminal zone’ — a place where the strict rules prohibiting social intercourse with strangers are relaxed. Certainly, your average train provides a fascinating snapshot of contemporary Britons, their dress, modes of speech, conversational tics, reading matter and raw emotions.

Over the years I’ve witnessed volcanic rows and filthy joke competitions; once interrupted coitus when opening an unlocked toilet door and been moved by the tears of solitary women as they contemplated some loss. I’ve glimpsed the rich and famous, from the late Tony Benn to Newcastle’s own Peter Beardsley and once encountered Hugh Grant and Jemima Khan wearing worried frowns as they realised they were a train length from their first-class comfort zone.

Many people seem to prefer the collective ethic of railways to the individualism of the car, though commuters might disagree. One of my favourite pieces of railway literature is Roger Green’s Notes From Overground, an aria to the servitude of the commuter which misquotes Rousseau’s dictum: ‘Man is born free, but is everywhere in trains.’ But if it hadn’t been for Green’s daily grind I’d never have known that some inspired British Rail functionary once named the network’s freight wagons after various forms of sea life: grampus, dogfish, haddock, ling, lamprey. I haven’t spotted them for years now but then fish stocks are declining everywhere, even on the railways.

This richness makes it more irritating that railways have been so mucked up in my lifetime, culminating in the utter b******s of privatisation and lately the cancellation of the HS2 extension.

The essential point is that politicians consistently miss the point: railways aren’t the transport system of the past but the future. Hardly surprising: these people usually travel in ministerial limos — or helicopters in Rishi Sunak’s case. Mrs Thatcher famously never travelled by train, though perhaps for her the phrase ‘fellow-traveller’ had a sinister meaning.

To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive, said Robert Louis Stevenson, who crossed America by train in 1879.

Railways have come to be seen not as a glory but as an inconvenience and governments continue meddling and making worse. This is not happening elsewhere. High-speed networks have been built all over the world, despite their cost. Why such a disparity?

I suppose after the war the shattered infrastructure of Europe had to be rebuilt and countries like France and Germany got into the habit of rolling investment, whereas Britain became increasingly influenced by the consumer culture of the US.

It’s indisputably easier to sell a lifestyle via a car than a train, or maybe I watched too many episodes of Mad Men. But it’s surely no accident that together the UK and the US resist the reinvention of the train, while everyone else gets it: railways generate economic growth, allow people to travel quickly and safely and cause less environmental damage. They help make societies viable, but our controllers don’t see it, part of a bigger collective myopia about our industrial heritage.

The place of my childhood, a region of shipyards and heavy engineering, no longer exists. It’s an exaggeration to say we don’t make anything anymore, but not to suggest manufacture is somehow regarded as past its sell-by date. As a result, the region is cleaner, with more amenities, but also a largely de-skilled economy dependent on the public and service sectors. I think we were sold a false prospectus. That makes me angry, because apart from anything else this new economy desperately undervalues the latent skills of the people among whom I live. They’ve so much to offer, as I know from personal experience.

Two members of my own family shared the skills that George Stephenson nurtured: the ability to take apart and put back together just about any working mechanism. It seems such skills are no longer valued in our culture.

The village from which I made my first journey to London in the Coronation year of 1953 no longer has a station of its own. The wooden hut in Shildon on which I sat trainspotting has gone, so too the rail works down the line where those fishy wagons were built. Schools of porpoise and shoals of herring once gathered here but they disappeared in the 1980’s, along with much of the North’s industrial base.

In my lifetime, the journey time to the capital from Newcastle has been halved from six hours to three, it seems in a curious way the distance has grown. Pioneering birthplace of so much technological innovation, the North East grows ever more remote from power and the people who wield it. Just one small consolation: the East Coast route is back in public ownership and the London Northern Eastern Railway lives on, with the addition of the Newcastle-based service, Lumo.

Now the wheels turn and my memory conjures up the Great Railway Journeys of my life.

Crossing the vast White Nile 6,000 kilometres from the Mediterranean on a grungy train from Nairobi to Kampala. Looking at a shimmering city across the water as our train halts at a red light before the last run into Venezia Santa Lucia. Marking out of 10 the immense grain elevators, gaunt architectural features of the Canadian plains, on the five-day journey from Vancouver to Toronto. Entering the Finland Station in old St Petersburg 80 years after Vladimir Ilyich Lenin arrived in 1917 to foment revolution, though our train wasn’t ‘sealed’. On the Amtrak South-West Chief from Chicago to LA, climbing the Rockies so slowly at one point Butch and Sundance could have robbed it without recourse to the horse — and two wonderful journeys closer to home, both from Inverness, west to Kyle of Lochalsh and the Isle of Skye, north to Thurso for Orkney.

One day I will make these journeys again from the Central Station.

Making sure of course I bought my ticket first…