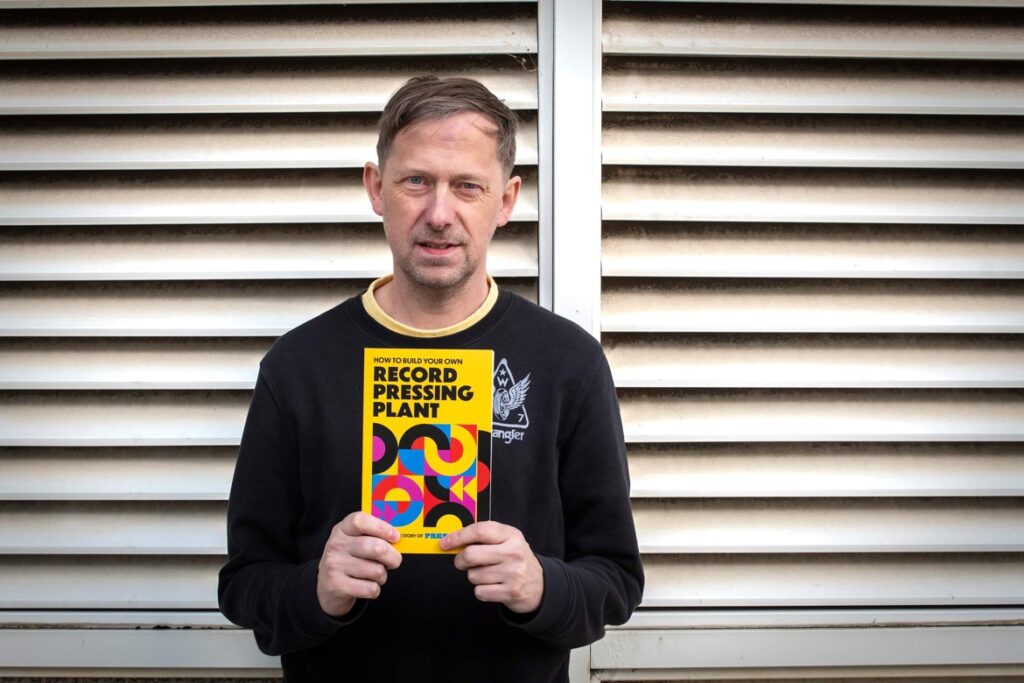

On the day, my book, How To Build Your Own Record Pressing Plant: The True Story of Press On Vinyl was published last November, I found myself sitting in the Teesside vinyl record factory’s boardroom looking across the TeesAMP Business Park as dusk settled over Middlesbrough’s less famous – but equally iconic – Newport Bridge.

I was musing about how co-founder Danny Lowe had once told me an unlikely sounding story about secret railway tunnels under the Tees that dated back to George Stephenson’s day and the very beginning of the steel revolution in the town.

It struck me that whether the story was true or not didn’t matter, and never had. What captivated me about Danny was his infectious enthusiasm, whether it was for folklore or his visions of manufacturing the world’s first bio-plastic records at the same location.

He also had plans to incorporate a food recycling station into the existing set-up so that the raw product for the bio-plastic could be produced on-site and an even longer-term vision to use the river itself to power all these ventures and even the whole of TeesAMP.

To me, it was his industrious nature and imagination that was most important, an extension of the historic legacy of innovation that may or may not have seen railway tunnels dug beneath the river all those years ago.

It might even be infectious. A year or so earlier when I had first approached Darlington based Butterfly Effect, it was to build on the entrepreneurial ethos even further by suggesting a record label should publish my book about the first year of the vinyl adventure.

Who better to publish books about music? And it’s certainly a story worth telling.

Danny and everyone else at Press On Vinyl were determined to make their small part of the music industry a fairer place for all. Press On’s reason for being, in a paragraph-shaped nutshell, was to limit print runs of vinyl records to 3,000 and to not let major record labels influence the queuing system by constantly bumping smaller artists out of the way.

At the time, stories were rife of artists not receiving their records in time for launch events, tours and release dates, and POV decided to provide a better alternative. Sister company Fairsound is a fantastic example of their approach — it allows acts and labels to press the exact number of records they need without any upfront costs.

Much like the steel boom of the mid-1800s that saw Middlesbrough grow from a small hamlet of 25 people in 1820 to a booming steel town that was producing one-third of the UK’s pig iron 50 years later, Press On Vinyl’s initial growth was rapid and something of a rollercoaster.

For some context, sales of Vinyl now outstrip CD sales for the first time since the late 1980s.

However, in early 2021, when the Press On Vinyl story begins, Middlesbrough was in something of a fug after decades of decline and underinvestment, exacerbated by Brexit which put an end to the EU grants that had previously topped up government funding.

The town centre was starting to resemble a post-retail dystopia to match the post-industrial flatlands along the Tees made famous by Margaret Thatcher on her walk in the wilderness in nearby Thornaby in 1987.

Danny had previously been an alarm fitter for a company involved with security at the controversial Durham Tees Valley Airport (as it was named at the time), while co-founder David Todd (Toddy to all and sundry) had been, more atypically, a foyboatman on the Tees itself.

If some readers are surprised to learn there are still foyboatmen (and foyboatwomen) in this day, Press On Vinyl in-house designer Tommy was plucked from the similarly Dickensian oeuvre of the steeplejack scene.

But I digress.

The genesis of Press On Vinyl was sometime in late 2020 when Danny and Toddy decided they wanted to release a vinyl record for their tiny Teesside-based digital record label, Goosed Records. As they tend to do with Danny, one thing consequentially led to another and in March 2021 they signed a 10-year lease on the Press On Vinyl building.

The fact that the funding wasn’t finalised when ink hit the paper offers a strong hint of the cavalier approach they would take to running the business during the next couple of years.

It wasn’t long before this attitude led them to being dubbed the ‘communist plant of the North East’, indeed a Cuban flag still flutters from the rafters of the warehouse as the pressing machines whir below. It’s just one of many examples of their insouciant approach to marketing in those very early days, much to the consternation, one suspects, of Colin Oliver whose Futuresound Group would later come to invest a large chunk of money in the company.

My book takes up the narrative at Middlesbrough’s Twisterella music festival in October 2021, when Press On Vinyl was announced to a wider audience through sponsorship of the Westgarth Social Club stage, and runs with it until the same festival in October 2022 when, rather serendipitously for me, FairSound was officially launched with another stage sponsorship.

In between, and among many other things, the first two pressing machines finally arrived on Christmas Eve 2021, the first record was pressed in late January 2022 and the in-house lathe was delivered in vexatious circumstances in June 2022, around the same time Danny and Toddy were desperately trying not to upset the music industry apple cart too much.

As of October 2022, the plant had pressed around 250,000 records… in this month, they’re about to press their one millionth.

While the hectic honeymoon period for the company may now be over — operations have been refined, profit margins prioritised and Danny is no longer at the helm — the underpinning ethos of Press On Vinyl remains the same, at least for now.*

And while things seem to be getting even more desperate locally, with the council seemingly at risk of bankruptcy and two of the town’s most popular DIY event spaces (the aforementioned and revered Westgarth Social Club and the popular Base Camp venue) both closing in the past year, strange things are happening.

Perceived established norms for live music such as a raised stage and a proper bar have gone out of the window and in their place anywhere and everywhere that can be used for creating, hosting and performing is suddenly being used for just that, and the more chaotic the better.

Even Teesside’s biggest music act, the archly named The Benefits, who have been making waves throughout the UK and Europe over the last year with their angst-ridden socio-political commentary, are way out in the far reaches of left field.

Experimental noise pioneers Industrial Coast have hosted anything-goes events in disused carpet factories, abandoned New Looks and tiny independent art galleries while the latest local hype band, Perfect Chicken, wear hazmats and balaclavas onstage repeating the mantra ‘you can’t run a town on stolen steel’.

And so we look forwards with hope and optimism.

The old industrial areas just to the east of the Press On Vinyl site are finally, if slowly, being redeveloped and Captain Cook’s Square in the town centre is being reimagined as an entertainment hub. Teesside University continues to grow both physically and reputationally, and a new mayor is making all the right noises.

Up, as the saying goes, the Boro.

*I contacted the company for some official updates on the 2022 figures and although these were not available, an upward curve can still be anticipated.

Kielder Water, Northumberland, which was opened by the late Queen in May 1982, is the UK’s biggest artificial lake by capacity, holding 44 billion gallons