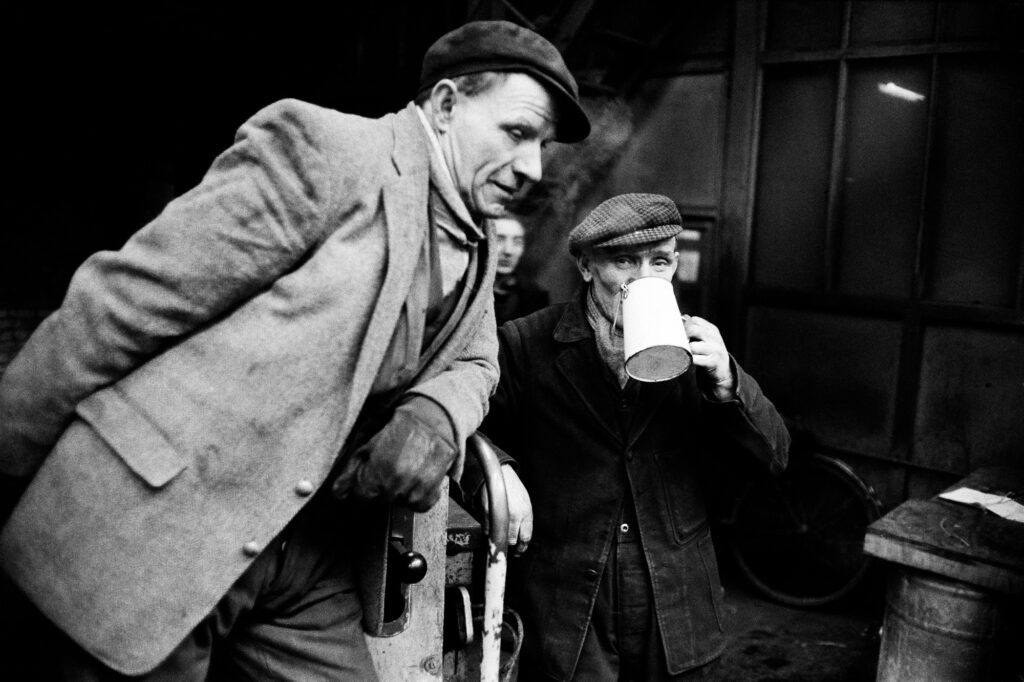

The winter of 1962-63 is remembered as the ‘big freeze’, one of the coldest on record. In some parts of the country snow lay metres high, bringing things to a grinding halt.

In Hartlepool, recording the worst unemployment figures in the country, hardship was piled on hardship.

William Gray & Co. had recently closed its yard after a century of shipbuilding, throwing 1,400 out of work, and it was the jobless angle that brought John Bulmer to the North East for the first time, a young photographer starting to make his way on Fleet Street and with a recently acquired taste for tough northern towns.

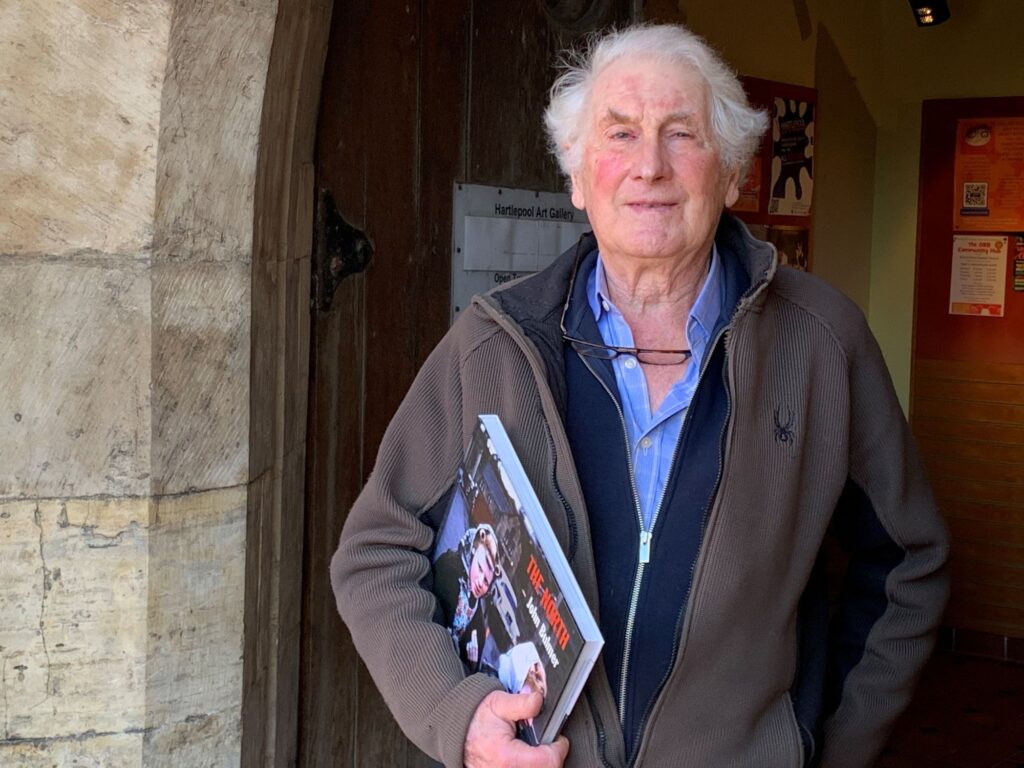

More than 60 years later, the photos John took that winter are on display in Hartlepool for the first time and he is back to provide context and share memories.

“I remember it very well because it was incredibly cold,” says the now 85-year-old.

“I couldn’t wear gloves to take photographs so holding metal cameras in a howling wind with bare fingers was very difficult.

“But I noticed the people gathering sea coal also had the same thing. They were holding shovels and they had no gloves.”

This is clear from the photos showing men bagging up coal and shouldering it from icy beaches to be carried away by bicycle or horse and cart.

John was on assignment for a magazine called Image which he’d helped set up when a student at Cambridge.

It seems to have been largely a labour of love because by that time he’d left the university, or rather been told to go. “Under a bit of a cloud,” as he puts it.

Photographs he’d taken of ‘night climbers’, daredevil thrill-seekers who scale the city’s academic buildings after dark, were bought and published by Life magazine.

The university authorities were not thrilled. Indeed, they showed John the door before he could graduate in engineering.

It wasn’t the end of the world. The young man from Herefordshire was already picking up work with the Daily Express and other newspapers.

“This is what I wanted to do anyway,” he says on reflection.

“I’d left Cambridge but still had connections with the magazine. We still owned it although shortly afterwards we sold it to Michael Heseltine.”

The circulation was tiny, he says, so the Hartlepool photos, although some do feature in his book The North (on sale at the gallery), haven’t been seen widely.

That only adds to the appeal of this Northern Light exhibition, something of a coup for gallery curator Angela Thomas and her team who were delighted when John responded positively to their approach.

John says his first experience of northern England had come with an earlier commission from Town, a trendy ‘60s magazine co-owned by Heseltine who would go on to make his name in politics after making his fortune in publishing.

Sent, with camera, to the Lancashire town of Nelson, he remembers the assignment as ‘like a voyage of discovery in a way’.

He likens it to his trips to Africa because ‘there was wonderful material at every corner’.

“I learned to love the industrial north and I’m not talking about the landscape which is something quite different,” adds John.

“I loved the people, the reactions. This morning I came down to breakfast in the hotel and the lady called me ‘darling’ and I thought, I’m home again!”

He has been back to Hartlepool several times since that first trip but still remembers how he was greeted in the depths of a freezing winter in a town on its uppers.

“The people were friendly. Their reaction was ‘How come you’ve come all this way to see us?’ rather than ‘Are you trying to exploit us? Go away’.”

John went on to have a fabulous career, summing it up with considerable understatement: “I had a good run for my money.”

Some of his most exciting assignments were for The Sunday Times which hired him to work on its then ground-breaking colour supplement.

He shared the inaugural front cover with fashion photographer David Bailey, his photo of a footballer surrounded by Bailey’s shots of the model Jean Shrimpton.

John’s prowess with colour photography, then seen as the preserve of advertising, had caught the eye.

“Obviously black and white photography was invented first but people had got used to taking photographs in black and white,” he remembers.

“The Sunday Times magazine was the first in the world really to use colour for documentary stories.

“Even magazines like Life ran documentary stories in black and white and used colour only for special features, fashion, advertising, pretty landscapes.

“Black and white photography was for the nitty gritty.

“Picture Post (the famous photo-led magazine of the 1930s to ’50s) had died about five years previously but those photographers were not used to colour.

“I was young and so perhaps better able to adapt to something technically different.

“The most important thing is that photography is a form of simplification. You have to simplify what’s in front of you, reduce it to a few elements.

“If you add colour, things get more complex. A lot of black and white photographers couldn’t eliminate extraneous detail so their colour photographs ended up too full of stuff, to put it bluntly.”

John travelled the world, often in the company of writers such as Philip Norman (later biographer of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones) with whom he drove the length of America’s fabled Route 66, and foreign correspondent Richard West who reported from Vietnam, Africa and Eastern Europe during the Cold War.

West was ‘a wonderful journalist’, says John.

“He was one of those very quiet people who appear rather incompetent so people spill the beans. If you appear all smart Alec, they shut up.”

When he died in 2015, John realised that despite having spent years in his company, he didn’t have a single photograph of him.

“It was that journalistic culture of wanting to be anonymous.

“It never occurred to me to photograph him doing his job which was silly because it would have been good to have something for his obituary.”

How times change!

John, who acquired his first camera aged 15 and whose hero was Henri Cartier-Bresson, left the Sunday Times magazine when told the new focus would be on crime, middle class living and fashion.

He moved into film-making, teaming up to make a documentary about Van Gogh with Swedish film star turned director Mai Zetterling who happened to be married to the editor of Town magazine.

Nowadays, says John, he doesn’t take many photographs, preferring to concentrate on making exhibition prints and books when the opportunity arises.

“I know quite a lot of old photographers who go around endlessly with a camera but most of the pictures they come up with are boring,” he says.

“I don’t want to take photos that are less exciting than ones like these.”

In Hartlepool his photographs are causing a stir.

“Is that the photographer?” asks one visitor excitedly.

Jacqueline Renwick, who has lived all her life in the town, wants to tell John she has just spotted her stepfather.

There he is, standing in a queue outside the Shipping Federation Office — known locally as ‘the pool’ – on Church Street.

Popping in for a coffee, Jacqueline had seen the date, 1963, and shuddered.

It had been a horrible year and not only because of the weather. Her cousin had died that year, aged just 24 and pregnant.

But suddenly her eye was caught by the figure in the queue. “It was a nice surprise,” she says.

Robert McLean, she reckons, was “a brave man”.

Her mother was a widow with five children when he became her second husband and they’d go on to have four more of their own.

She would have been 13 when the photo was taken.

Her stepfather, who died about 17 years ago, used to be away for months at a time as a merchant seaman but she remembers him as a kind hearted man who always offered money for sweets.

“You look at the photograph and wonder what he’s thinking. Is he thinking of his next ship?”

It won’t only be Jacqueline studying John’s photos carefully. They capture a moment in time, a tough time when resilience was called for and Hartlepool folk weren’t found wanting.

And while times may change, the urge to take photographs remains powerful.

Displayed near John’s images is work by photography students at the Northern School of Art, including black and white studies of modern sea coalers by Lee Bullivant — men with the same weathered faces but now with a car to carry the coal away.

Northern Light is at Hartlepool Art Gallery (open Tuesday to Saturday, 10am to 5pm; admission free) until May 4.

Durham Cathedral is the last resting place of the Venerable Bede whose Ecclesiastical History of the English People (c. AD 731) is one of the earliest history books.