It wasn’t just the Germans who knew Britain and her Allies were preparing to invade France in 1944 in a bid to end the deadliest conflict the world had ever seen.

The British public was also aware that plans were being finalised to liberate north-west Europe from Nazi occupation and destroy Hitler’s despotic regime.

What no-one knew — including the German high command — was where and when what was to become the largest amphibious invasion in history, would take place.

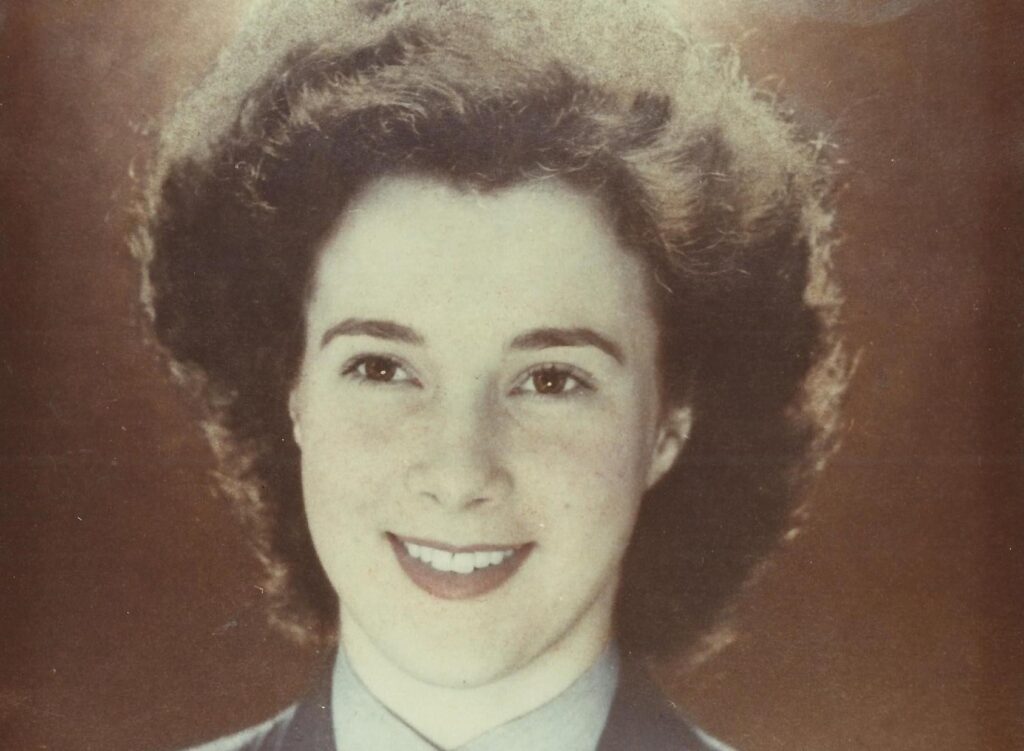

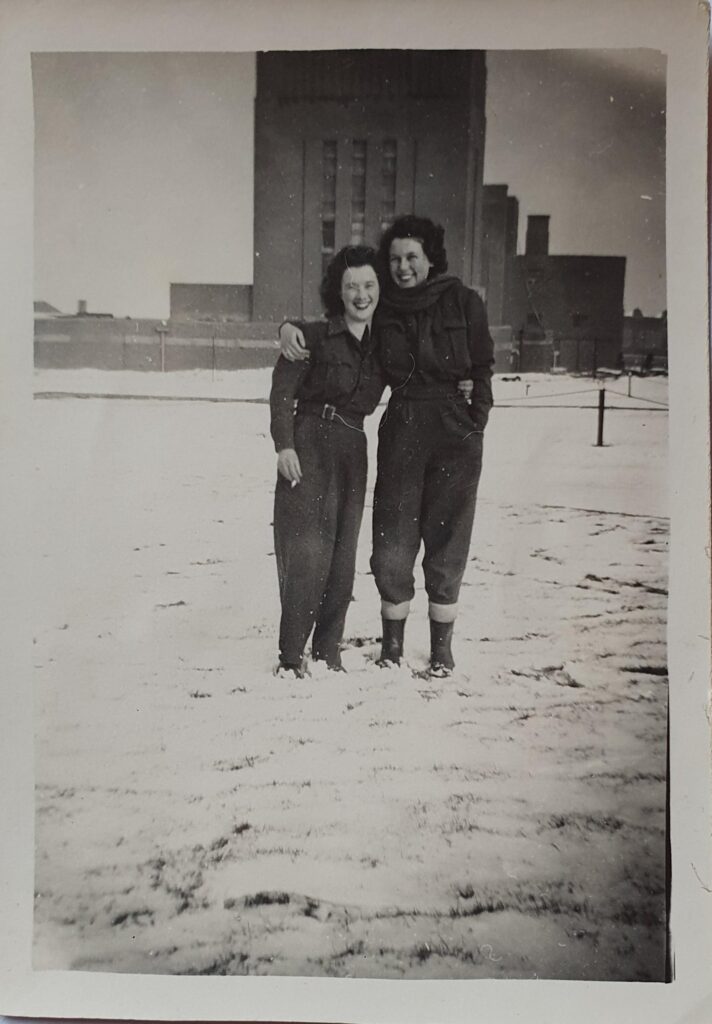

Betty Punshon had just qualified as a flight mechanic in the spring of 1944 when she was sent from training at Weston-super-Mare to RAF Filton near Bristol.

The Leading Aircraft Woman (LACW) in what was then the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), was just 19-years-old, and like many of her wartime contemporaries she admits to “living for the day.”

- Read more: A portrait of Derek

- Read more: Orchestral manoeuvres in the North

“You didn’t know what was going to happen or whether it might be your last, so you didn’t worry about tomorrow,” she said. “You did your work, had a good time, and didn’t think too far ahead.

“It sounds awful now, but I don’t remember being particularly affected by what was happening. We were young, and I don’t think when you’re young you take things as seriously as you perhaps should.”

Dances, impromptu gatherings, and social get-togethers at the local pub were a big part of Betty’s life when she was off-duty.

It may seem a callous attitude now, but for Betty and her WAAF colleagues, it was how they escaped the pressures and dangers of constant aerial bombing, rationing, and loss as the home front became the frontline, and the boundary between life and death was eroded.

But soon after arriving at RAF Filton, Betty was to receive a sobering reminder of the realities of war — and gain a disturbing insight into what the Allies were planning to undertake to turn the tide of the conflict in Europe.

Now 99 and living in Whitley Bay, North Tyneside, Betty recalls her work detail suddenly being ordered to remove all the seats from the twin-engine Avro Anson aircraft they had been servicing.

Well used to obeying orders, they didn’t question the unexpected request, and got on with the fiddly task of unbolting each plane’s six lightweight leather and tubular metal framed seats.

“It was only later that we found out the planes were to be used for medical evacuation flights for our boys,” Betty recalls. “It was then that we knew something big was being planned, although we didn’t call it D-Day at the time.

“I can’t remember how far in advance of D-Day we were asked to remove all the seats, but they were obviously expecting to have to deal with seriously wounded soldiers who would need to be flown back quickly.”

Betty says the Avro Anson was a small plane compared to the better known Lancaster, Halifax, and Stirling, and was mainly used for training and reconnaissance operations during the war.

It is this, she believes, that made it suitable for transporting the injured as the Allies broke out of Normandy and pushed the Germans east.

“I’m not sure how we first heard that the invasion was underway; if we were told or if we heard it on the wireless,” Betty says. “But the casualties started arriving. We weren’t supposed to see the injured soldiers being brought back half dead. I don’t think it was thought suitable for us to see.

“We were sent into the hangars and told to get on with other jobs. The war was still being fought and the RAF was still going up, and it was our job to ensure the planes kept flying.”

Crews habitually had to make a quick turnaround. “We’d often find ourselves taking the wheel chocks away as the crews went off on another sortie,” Betty explains.

“They didn’t always come back. But you didn’t dwell on it. It may sound awful now, but it was often a case of a quick toast in the Mess to their memory and back to work.

“We worked hard and we partied hard. The Americans were stationed near RAF Filton, and they used to join us for dances. That’s when I learnt to jitterbug.

“It was important that we kept morale up, even more so after D-Day. We wouldn’t have won the war if we’d all fallen apart. Everyone had to get on and do their jobs — and we all felt we were doing a good job.”

Betty admits she was thrown in at the deep end and recalls whilst at RAF Filton being asked to do watchtower duty.

“One time I had to bring an aircraft in for refuelling as the crew was going on another raid. I think it may have been either a Lancaster or a Stirling. It had been wet weather, and I directed the aircraft to a particular patch of ground near the watchtower, and it sank! The plane was so heavy the wheels became trapped in the mud.

“The pilot gave me hell! I remember crying my eyes out as he yelled at me. Of course, the plane had to get back out, so they had to use the tractor to pull it free.”

Betty can laugh about the incident now, but says that at the time it felt like the end of the world. “You have to remember, everything you did could have potentially serious consequences, so you couldn’t afford to make mistakes or cut corners.”

But as was the case for so many, the war offered Betty the chance to make something of her life and escape what had been a difficult childhood.

Born and raised in Northern Ireland, her mother had died in childbirth whilst Betty was still young. Money was tight, and at the age of 14 she had to leave school to work on the family farm.

But at 16 in 1941, she moved to Belfast with her elder sister Greta, to work at the Short and Harland factory, which was involved in making Sunderland flying boats and the long-range heavy Stirling bomber.

Betty learnt to use a lathe and helped make the cylinders for the landing gear of the Stirlings, as well as munitions.

It was in Belfast that the then teenager first came face-to-face with the dangers of war when in April and May 1941 the German Luftwaffe targeted the city’s shipyards and engineering works.

Belfast was thought to be out of range for the German bombers, so had been left largely undefended apart from a few barrage balloons located at strategic sites.

Betty was living with Greta near the docks, and found herself in the middle of the raids. One night whilst running to the shelter she was so scared she was physically sick. A passing soldier offered her a drink of whisky to calm her nerves.

She says: “That was a really bad night. The planes were right overhead, bombs were falling everywhere, and there were terrified people running in all directions trying to find shelter.

“I look back now and it’s difficult to believe the things I had seen and been through by the age of 16. Today’s 16-year-olds wouldn’t know how to cope with what we went through. They’d be traumatised. But the next day we went to work through the rubble and got on with things.”

Betty had set her sights on joining the WAAF, however, inspired by the plethora of recruitment posters dotted around Belfast encouraging young women to serve alongside “the men who fly.”

She joined at the age of 18 alongside Greta, and together they sailed to Liverpool to begin their training.

Betty says it was only years later that she appreciated how dangerous that crossing was, with German U-boats patrolling the Irish Sea attacking Allied shipping.

Greta was invalided out of the WAAF with TB shortly after arriving in mainland Britain, but Betty was sent for her flight mechanic training, which she found fairly easy having already worked at Shorts in Belfast.

At RAF Filton she looked after the Avro Anson, twin-engine Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle, and Hawker Hurricane. Stationed just five miles from Bristol, air raids were a constant menace. But Betty never thought she was going to die.

“I was more worried about making sure I had some lipstick handy in case I met a good looking lad in the shelter!” she says with a twinkle in her eyes.

Betty was later posted to RAF St Athan in the Vale of Glamorgan, before being sent to RAF Wig Bay on the western shores of Loch Ryan near Stranraer, where she was tasked with servicing the Sunderland and Catalina flying boats helping protect the Atlantic convoys sailing between Britain and North America.

There were no runways, just huge maintenance hangars along the shore, with work on the planes mostly taking place on the open water of the loch. Betty would be rowed out to the seaplanes where she would rivet the wings, ensure everything was properly sealed and watertight, and remove the build-up of barnacles.

- Read more: Why language must matter in a civilised society

- Read more: My life through a lens: Helen Rowlands

Betty remembers feeling tiny beside the massive planes, which were large enough to accommodate a small kitchen and bunk beds for use by the crew, who would spend days at a time patrolling the North Atlantic.

She still has a soft spot for the seaplanes, and describes seeing them skimming just above the water and then lifting off feet above her head, as one of the most exciting spectacles she’s experienced.

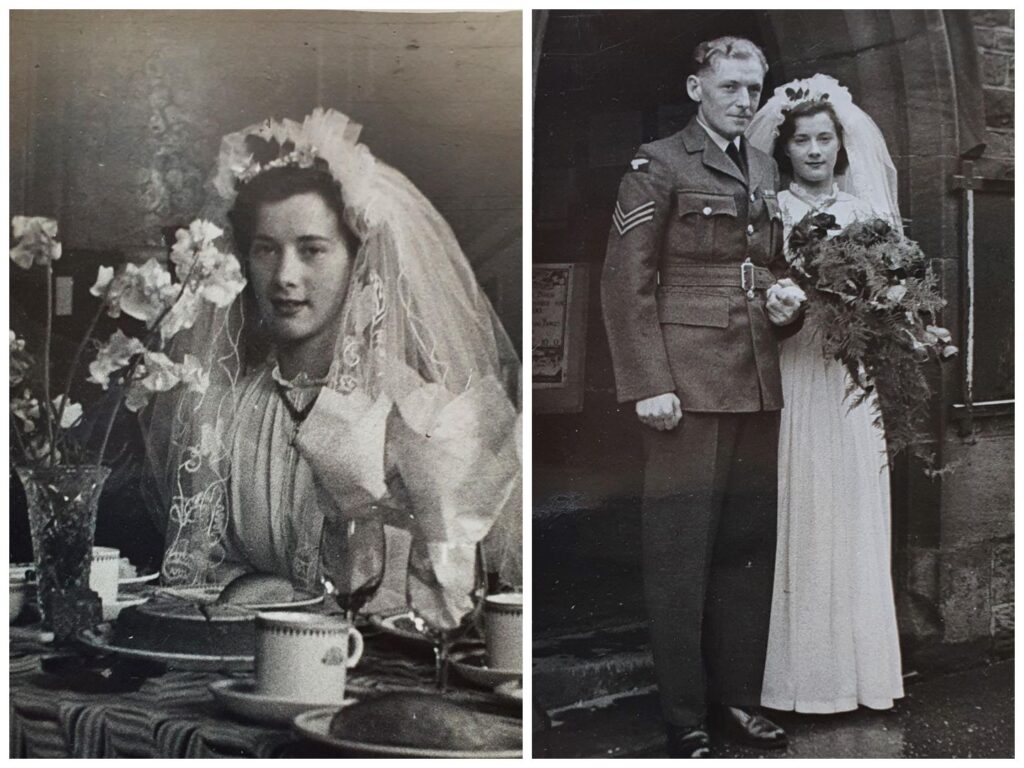

It was whilst she was at Wig Bay that she met her husband, Flight Sergeant Fred Punshon. It was not an auspicious first meeting, as he had needed to tell her off. But that first encounter didn’t stop romance blossoming, and the couple married in Fred’s hometown of Whitley Bay in 1947.

He remained in the RAF for 38 years and after moving around the UK and being stationed abroad, the couple eventually settled on the North Tyneside coast, where Betty now lives in a retirement apartment overlooking a local primary school.

As she prepares to mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day with veterans from the Whitley Bay Comrades Club, she confesses she is spending more time reflecting on her wartime service and the freedom, peace, and prosperity her generation fought for.

But she says: “Now, with everything that’s going with Ukraine and Gaza, I look at the little children walking to and from school each day and wonder what it will be like for them when they grow up.

“What sort of world will it be?”