This was the commission: The Gordon Burn Prize is going to be hosted in Newcastle from now on, so could I write something about him and his home city?

Yes, but warily.

Warily because I wasn’t sure how Burn felt about Newcastle. I knew he grew up in the city’s west end, but he left when he was 18 to study sociology at Birmingham College of Commerce and never lived here again, settling in London, where he wrote books about Fred West, the Yorkshire Ripper and Alma Cogan — winning the Whitbread Prize for that one in 1991 — before he died in 2009.

Hence I didn’t want to gush about his relationship with his home town if it wasn’t how he felt. Equally, I didn’t want to imply the opposite as I had no idea if that was true either.

I wasn’t alone in my doubts.

Joe Sharkey, who wrote Akenside Syndrome, a book about Geordie identity, suspected Burn of being ambivalent about Tyneside, citing a piece Burn wrote for The Guardian in 2005 which included a section about poetry readings at Morden Tower, part of the city wall.

In that piece Burn recalled leaving the tower and having to walk against the football crowd arriving at nearby St James’ Park. “This always seemed a reasonable direction in which to be heading,” Burn wrote.

In the same paragraph, Burn also reflected on his teenage self: “I was simultaneously wracked by, and revelling in, the realisation that I belonged nowhere; that culturally, and in class terms, I was a displaced person.”

How do you write about that person and that place?

The sanctuary of agreed facts. Burn was born in Newcastle in 1948. He grew up in a terraced house with an outside toilet. His dad worked in a factory on the Tyne, his mum was a cleaner, he went to Rutherford Grammar School. “I was a conventional product of the system, a standard roll-on, roll-off grammar-school achiever,” Burn said.

Then came the tower and the poets, and the sudden awareness there was more to everything.

“It is impossible to overstate the impact the Morden Tower had on me as a booksniff sixth-former,” Burn wrote in 2000.

Connie and Tom Pickard (Tom stayed ‘good pals’ with Burn and read a poem at his funeral) organised the poetry readings, attracting big names like Alan Ginsberg. The tower was the first time Burn realised ‘writing could be something more than a set text to be slogged through’.

In the summer of 1967, Burn sought further inspiration, heading to the US, paying $99 for a 99-day unlimited bus ticket.

He read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood on the Greyhound bus and worked for Rolling Stone magazine, which was still based above a garage back then. “My interest in American New Journalism was one of the main reasons why I wanted to work for the magazine,” Burn said. “I was very aware of writers like Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese and Joan Didion.”

Having returned to Newcastle, he applied what he had learned by writing a piece about Norman Cornish, revealing his rejection of the moniker ‘pitman painter’.

The article ran in The Journal, in 1970, and in The Guardian. “Why do people call me a pitman painter?” Cornish told Burn in his home in Spennymoor. “Why should they? I mean, Strauss worked in a bank at one time but would you call Strauss the bank-clerk-musician? No, you wouldn’t.”

There is a danger for Newcastle writers of becoming a Geordie writer, pigeonholed by subject, expectation, limits.

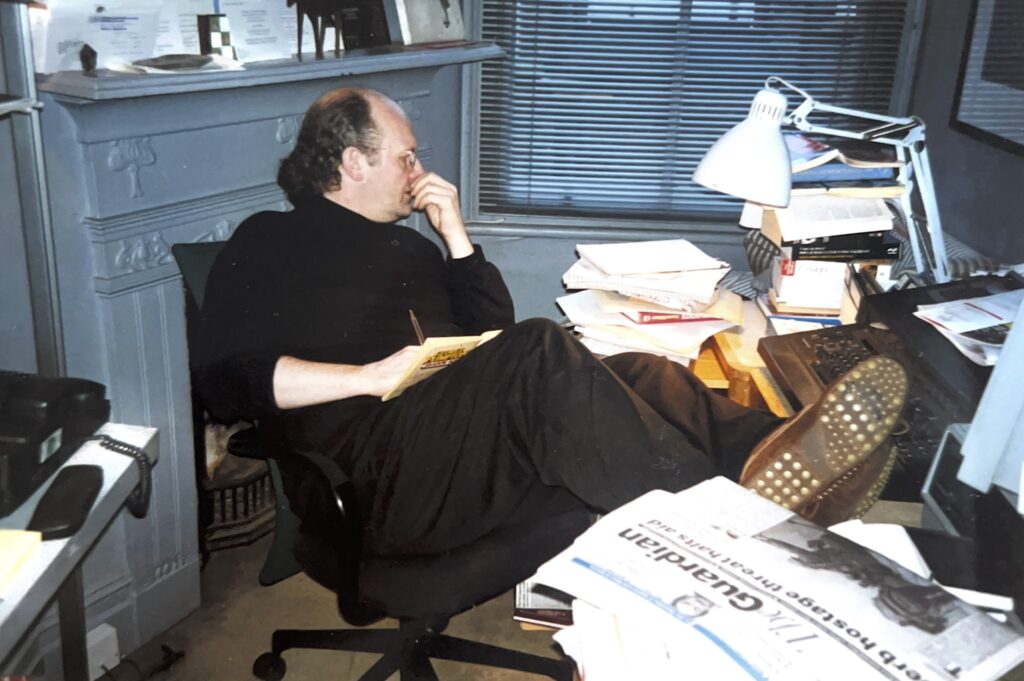

Burn never slipped into that; he was always Gordon Burn, a writer. Inevitably, as a working-class man from Tyneside, he was ‘the outsider’ in London journalism when he first moved there, according to his widow, Carol Gorner.

That may have benefited his journalism, but he never overplayed it. Newcastle was only ever in his work carefully, reservedly. He was not a sentimental writer.

As Robert Colls, an academic and Burn’s friend, told me: “There are people, kind of Geordie types, and I might be one of them, who are very quick to make the connection and then talk in maybe even a nostalgic way about being Geordies, but Gordon wasn’t like that. He was too hard, intellectually hard, to go in for any kind of nostalgia.”

Burn was sharp to the use of Geordie identity. When he interviewed Sting for Arena magazine in 1988, Burn wrote: “The first thing he said, though, at that first meeting, was that he remembered me from the top of the number 34 bus to Newcastle.

“It was possible. I had gone to school 50 yards from his. I should have been flattered. Instead, I suspected (probably correctly) that I was being softened up.”

In a piece for The Guardian in 2005 about artists Jane and Louise Wilson, twins from Newcastle, Burn suspected they were using their roots: “They tend to address the loftiest art-world panjandrums as ‘pet’, and still refer to cigarettes, as hardly anybody in Newcastle ever does any more, as ‘tabs’.

“This has the (probably intended) effect of encouraging people to underestimate them.”

I only ever heard Burn speak once, an audio clip on the Backlisted podcast.

In that clip he had a soft, grammar school accent. There was no hint of hamming it up or toning it down, though Gorner said he impulsively dusted off his Geordie vocabulary when they visited the city, returning to a past life.

“He just seemed to be very able to be one person in London and another person in Newcastle,” she said. “He’s still the same person obviously, but he didn’t seem to be conflicted by it or anything. He always loved Newcastle.”

Burn regularly returned to see his parents.

He would take Gorner to his dad’s club, the Nova Castria, or later to the Free Trade Inn; he loved the Lit & Phil, of which he was a member; and he loved the town moor and its cows.

“He would always point them out to me and I’d go, ‘Yeah, I saw them last time’,” Gorner laughed, adding that when she suggested to him there must be more to see in the city, Burn resisted, telling her, “This is my Newcastle.”

The moor and cows appeared in Burn’s 2003 novel The North of England Home Service, which he wrote in Newcastle while his father was ill.

It was about a comedian returning to the north from London — ‘slunk home to the North East to live’, Burn wrote. Burn never showed any intention of returning to live in the city, but Gorner said he always ‘adored it’.

“I used to say to him, ‘London is my home, it’s not home for you is it?’ And he went, ‘No, Newcastle’s my home’.”

Eighteen months before he died, Burn and Gorner bought a cottage in Longformacus, just across the border in Scotland, not far from Embleton where they stayed when the heating in his parents’ flat became too oppressive.

The cottage was going to be a place for him to write in. Tom Pickard wondered if Burn was ‘skirting’ his home town by buying the cottage, though Gorner said it was New York rather than Newcastle that he thought of moving to.

Among Burn’s photographs is one of him as a boy with his pals among the terraces and alleys, now gone, looking like a ‘Geordie and a bit of a lad’, as Damien Hirst, one of Burn’s favourite subjects, once described him.

Over the years, the photos show him diverging from the Geordie norm. One shows him in Los Angeles in the 1960s, where he spent time with his cousin, Eric Burdon, lead singer of The Animals, the Newcastle band who sang, ‘We gotta get out of this place, if it’s the last thing we ever do’.

Was Burn escaping when he left Newcastle, or looking for something?

“He was trying to get to what was real and he was trying to deal with what was in front of his nose,” Colls said.

“And as Orwell said, sometimes seeing what’s in front of your nose is the hardest thing to do, and what was in front of his nose was a region beginning to break apart and get demolished, and pits were closing, terraced houses were being pulled down, things were changing fast, and it certainly wasn’t where Avant Garde literature or art was happening, so off he went to London.”

Newcastle transformed in Burn’s absence as it tried to find its post-industrial role. In Fullalove, Burn’s 1995 novel about a journalist, he wrote: “When I grew up as a boy in the north of England, there wasn’t much, so when I arrived in London I had nothing, and I forgot what little I had up there. The hospital where I was born is now the Happy Dragon Chinese restaurant. The school that I attended is now a discount mall.”

“I used to say to him, ‘London is my home, it’s not home for you is it?’ And he went, ‘No, Newcastle’s my home’.”

Carol Gorner, Gordon Burn’s widow

Burn’s childhood home on Hamilton Street was demolished. His dad’s club, the Nova Castria, went. Rutherford Grammar School went. The brewery he grew up beside — ‘The earthy sweet smell of yeast from the Blue Star brewery’ he wrote in Alma Cogan — went. The coach station, his route into and out of the city, went. Morden Tower is still there, in a dingy alley used for rubbish from Stowell Street’s restaurants, locked up, out of use, decaying.

The erasure will continue, but having the Gordon Burn Prize in Newcastle is a minor act of preservation.

It will let people know that a great writer once lived here. His name was Gordon Burn and Newcastle meant something to him, just as he should mean something to those who live here now.

Andrew Hankinson, born in the North East and based in Newcastle, is an author, journalist and host of a podcast dedicated to non-fiction. His books include the award-winning You Could Do Something Amazing With Your Life (You Are Raoul Moat). He is on this year’s Gordon Burn Prize judging panel.

The Gordon Burn Prize, recognising literature that is ‘forward-thinking and fearless’, was first awarded in 2013. It is supported by Newcastle University, the Newcastle Centre for Literary Arts and the Gordon Burn Trust. The winner of the prize, this year worth £10,000, will be revealed at Northern Stage on March 7.

On 3rd February 1879 Newcastle’s Mosley Street became the first road in the world to be lit by electric lighting, showcasing the potential of Joseph Swan’s incandescent light bulb.