Wherever you travel in the world you can bet your bottom dollar you’ll bump into a fellow Geordie, Mackem, or Sand-dancer.

My latest such encounter was on the other side of the globe with a 20-year-old lad from a rather famous Newcastle family. But he had perished more than a century before in the most dramatic circumstances.

Edwin Bainbridge witnessed an awe-inspiring natural phenomenon which would change New Zealand’s landscape and ultimately cost him his life.

- Read more: Jill Halfpenny – Reimagining a life after unimaginable loss

- Read more: Culture and cuisine on Dance City’s menu

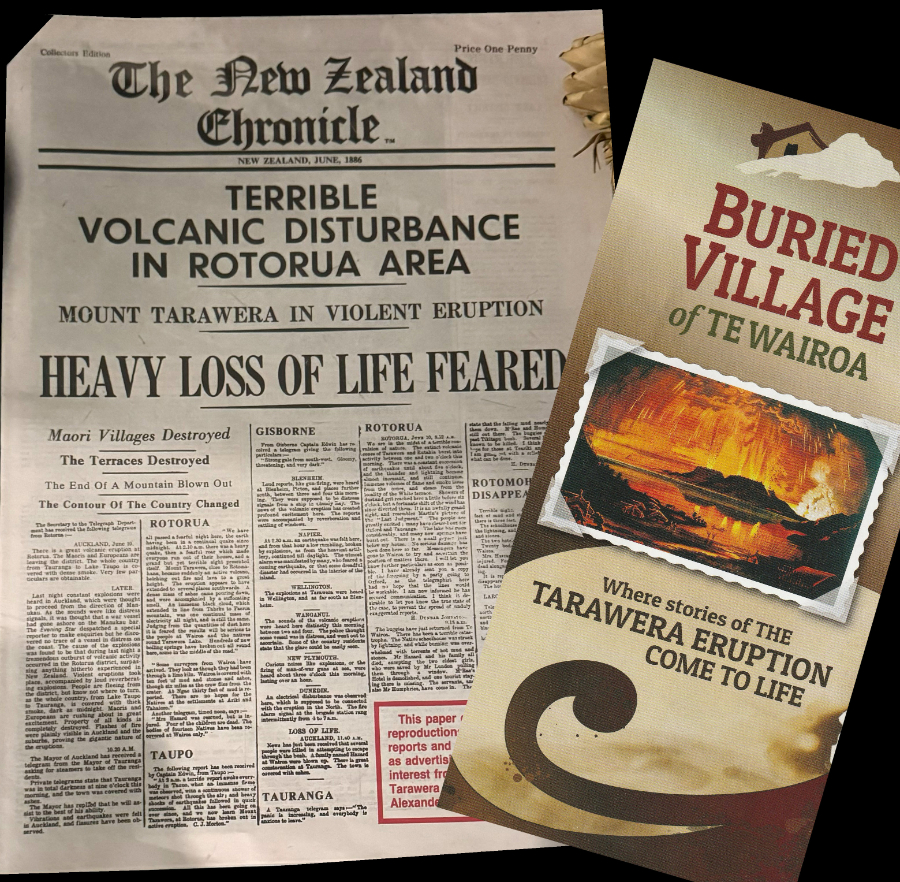

This Tyneside youth was the last European to see what some considered the eighth wonder of the world before it was consumed by a massive volcanic eruption. June 10, 1886, was the southern hemisphere’s Vesuvius moment.

The fact that Edwin was in the wrong place at the wrong time was itself the result of multiple tragedies within his own family. He’d escaped immense sadness at home by embarking on what was to be, literally, his trip of a lifetime.

I came across his remarkable story while visiting the buried village of Te Wairoa. This was where Edwin wrote an unfinished note to the world as he realised he would not survive the onslaught of ash, mud and rocks that were cascading out the sky.

How come I’d never heard of the tragedy that befell Edwin Bainbridge, an heir to the famous Newcastle department store?

My great-grandfather most likely would have done. He was just a few years older than Edwin and was a city-centre draper, just around the corner from the famous Market Street store. I decided to research it a bit more and it is fascinating.

The disaster was headline news in Newcastle, even before the city realised it had claimed one of its own. A day after the eruption, newspaper sellers on Newcastle’s Mosley Street were shouting: “Earthquake in New Zealand!”

When details of Edwin’s death emerged four days later it would shake the already fractured foundations of the Bainbridge family to the core.

Edwin and his siblings had been under the wing of his grandfather — the founder of the famous store, now part of the John Lewis chain — after they were orphaned. He was only seven years old when his father died of typhus. His mother passed away a few years later.

Further tragedy followed as he grew up. His brother Cuthbert, just two years his senior, died from an ‘accidental gunshot wound’. My research points to suicide and mental illness. The former was still a crime, the latter another Victorian taboo.

Archives reveal Cuthbert had been sent to a private mental asylum in County Durham and only days after being transferred to another institution in Dumfries he was found dead from a gunshot wound to the head. He was 20.

- Read more: Capturing all the fun of The Hoppings

- Read more: Poetic rebirth for prehistoric predator

The Scottish Procurator Fiscal didn’t pursue an investigation to find a killer and I can’t find any death notice in the North East newspapers, which is unusual for such a prominent family. It feels like it was hushed up and it is not unreasonable to conclude that Cuthbert died at his own hands in a troubled state.

The Bainbridges were a devout Wesleyan Methodist family. Back then suicide was seen as a crime against God so one can only imagine the impact it had on them. Edwin’s sister, May, passed away just two months later from what is oddly described as ‘decline’.

Not surprisingly, it was decided best for Edwin to get away from it all and so he embarked on his fateful round-the-world trip.

Reaching New Zealand, he headed to what was a natural wonder, a sight worthy of any wealthy European tourist: the white and pink terraces of Lake Rotomahana.

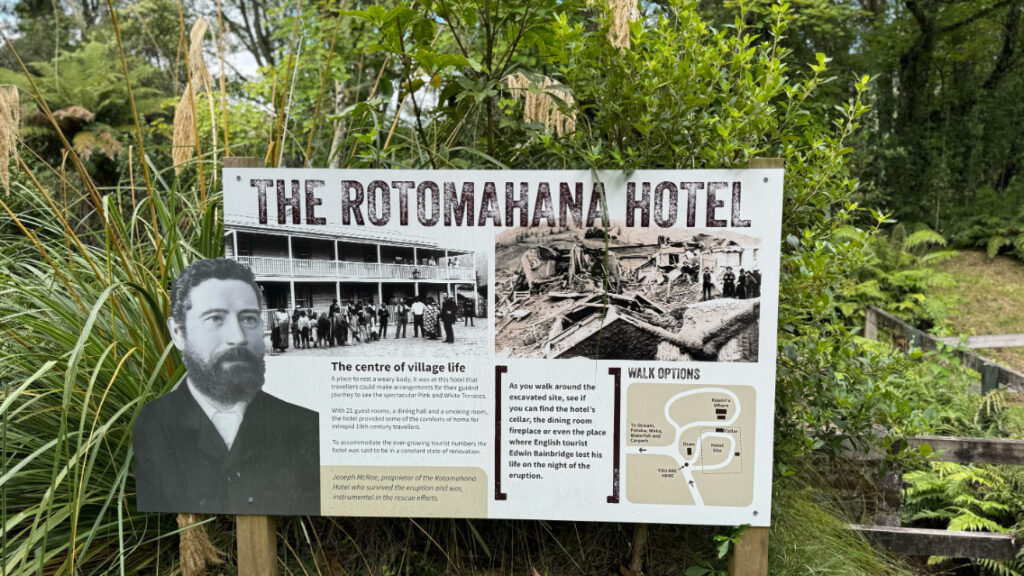

Back then the hot spring waters created dramatic silica terraces and pools in which you could bathe. To reach them you’d stay in Te Wairoa — a remote village that was built around the fledgling tourist industry.

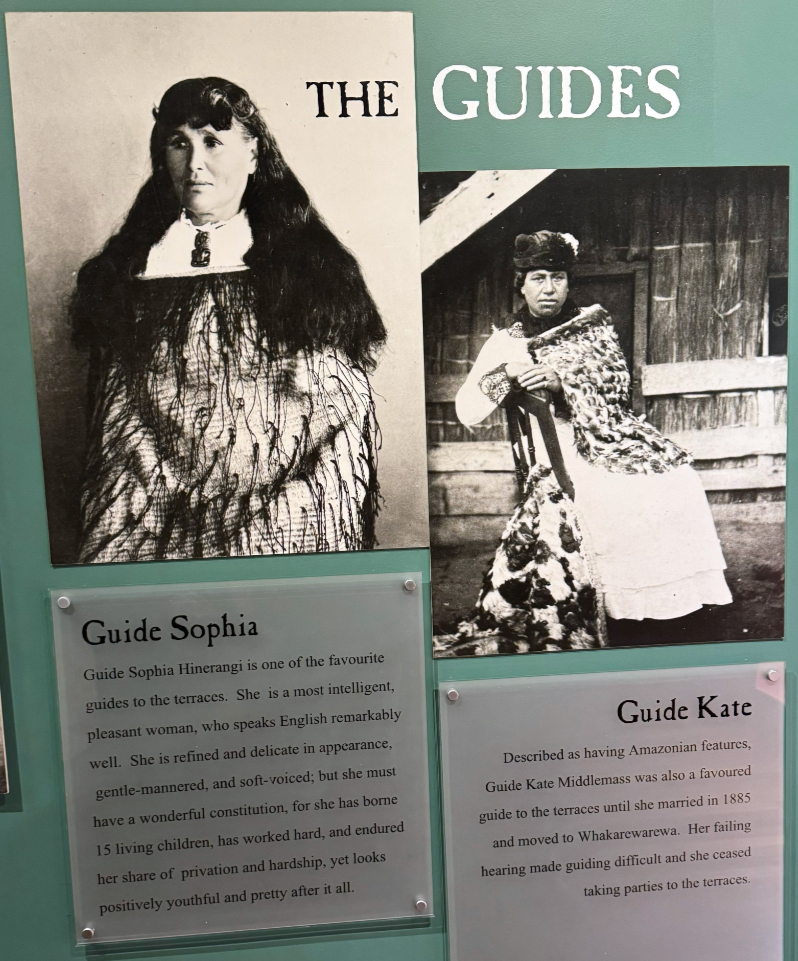

Māori guides would take you across a lake and then on a trek to this natural marvel. One of the most famous guides was Sophia Hinerangi who accompanied Edwin on what would be the last-ever trip to the terraces.

She had reported seeing a strange wave travel across the lake a few days previously. Could it have been a mini tsunami triggered by an early underground tremor?

There were also tales of a mysterious sighting of a Māori war canoe. No such vessel existed on the lake, so it was seen as a bad omen. Yet nobody fully understood what terrifying spectacle was about to be unleashed.

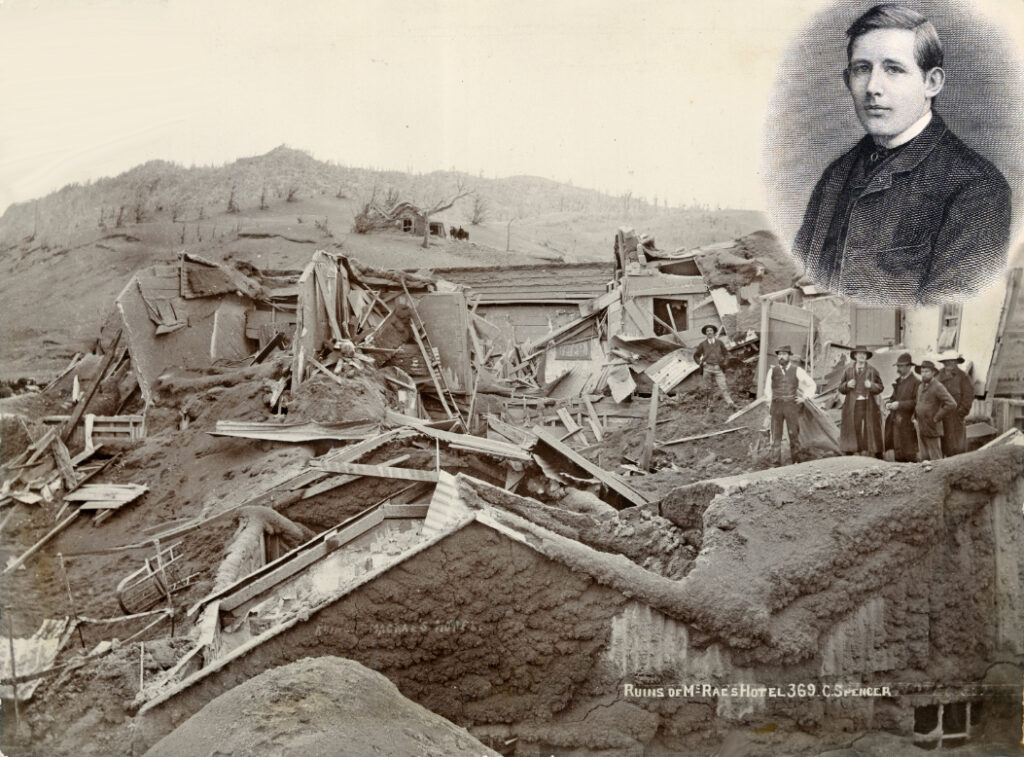

Edwin returned to Te Wairoa and was staying in one of the village’s two hotels.

As it was winter he was the only guest. In the early hours of June 10 the earth began to shake. Joseph McRae, the hotel owner, urged Edwin to dress and join the other villagers to see what was unfolding from a nearby vantage point.

In the distance Mount Tarawera had erupted.

The hotelier later recalled: “We saw a sight that no man can ever forget. Flames of fire were shooting up fully a thousand feet. There seemed to be a continuous shower of balls of fire for miles around.”

Another witness said: “We did not feel at all frightened then. The view was magnificent. The whole place was glistening with lightning.”

After ten minutes they all decided to return to the hotel as it had started to rain. Only it wasn’t droplets of water, it was the first signs of ash, mud and scoria — rock ejected from the volcano — that would eventually bury the village up to two metres deep.

They huddled together in a dining room as the calamity of their situation became clear. With the weight of the falling debris the hotel roof heaved, rooms started to collapse around them.

What had begun as a distant spectacle was now terrifying and apocalyptic.

One of those present said Edwin shared with them how he’d lost his parents, brother and sister: “Bainbridge said the disaster would soon be heard of in England and whether he lived or died it would have a great effect on his family.

“He said this in such a manner as to lead me to think he felt positive he would not himself escape the terrors of the night.”

Edwin, with his devout religious background, suggested he lead the group in prayer, telling them he believed God had given them this respite before the end came that they might prepare to meet their maker.

As a large section of the hotel gave way, Joseph said they should run to Sophia’s house which was immediately opposite. Māori dwellings, called whares, have steep roofs and the falling volcanic debris would more easily fall away to the ground.

Joseph recalled: “It was so dark that we could not see our hands before us and we directed our way by instinct.”

Although Edwin had been one of the first to make for safety, he never arrived.

As a visitor, it seems he couldn’t easily get his bearings in the confusion. Rather than dash straight out into the unknown he had edged along the front of the building only for the veranda, which provided some cover, to come crashing down on him.

His body was found entombed beneath the thick blanket of mud several days later.

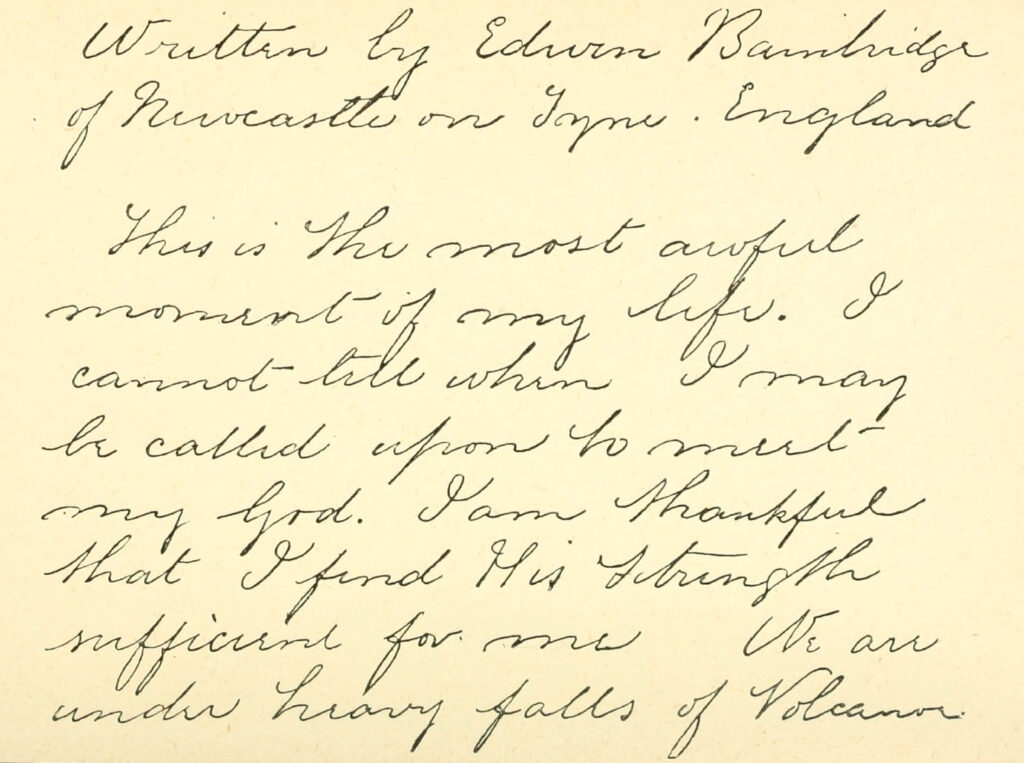

In the desperate final hours sheltering in the hotel contemplating their fate, Edwin had written a final note, reproduced below.

It reads: “Written by Edwin Bainbridge of Newcastle upon Tyne, England. This is the most awful moment of my life. I cannot tell when I may be called upon to meet my God. I am thankful that I find his strength sufficient for me. We are under heavy falls of volcan…” And there, it seems, he was interrupted.

As if he intended to come back to it, the note was placed in his writing case. Despite all the destruction, it was later found intact in the crushed wreckage.

Edwin was one of around 150 people who died in the eruption of Mount Tarawera. It had upended the landscape, including Lake Rotomahana, which is now ten times its original size.

I took a cruise on the lake to see the Tarawera crater. Somewhere beneath me in the depths I imagined the dazzling white and pink terraces that had drawn Edwin to be at the same spot 138 years previously.

There have been reported sightings of the infamous terraces using the latest underwater search equipment, but nothing is proven. The sheer force of nature that night may have destroyed them altogether.

Today the area is still alive with volcanic fissures and geysers, as you’ll see from the On the QT podcast I’ve made to accompany this story.

It’s easy to see why Edwin would have marvelled at the sights, sounds and smells of this active landscape.

Edwin’s death certificate has uncanny echoes of his brother Cuthbert. Their shared surname, Bainbridge, the same age — just 20 and officially both recorded as ‘accidental death’. Each a tragedy yet buried oceans apart.

Edwin was interred alongside some of the other victims of the Tarawera eruption. The cemetery overlooks nearby Rotorua, the town that now attracts tourists to wonder at its famous geyser and hot springs.

His grave is rather grand and bears his image. His family had a local methodist church built in his memory in 1909 and, although the original building is no more, his name lives on in the new “Bainbridge centre”.

It’s hard to imagine how much pain and suffering Edwin had endured in the mere two decades of his life. Clearly his faith saw him through those tough times.

Young as he was, nobody could say he hadn’t lived. He had traversed the globe. On one remarkable night, he willingly witnessed the power and glory of nature as it put on a spectacle few have ever seen, only to fall victim to its aftermath.

To his surviving relatives it must have felt like a continuance of a family curse, to the coroner it was an accident. To him, in his last hours, it seemed inevitable. Perhaps it was quite simply, luck and fate rolled into one.

1 thought on “Eruption which changed the world and cost Geordie tycoon his life”

Fascinating story – thanks Chris!