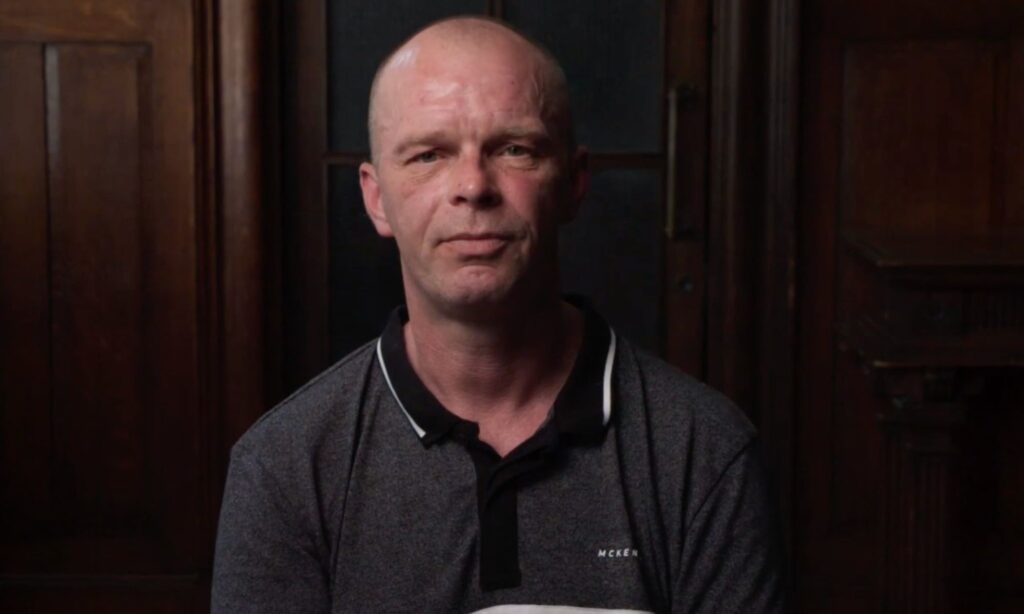

Outside the North Shields pub on a grey morning, Earl John Charlton is waiting — short-sleeves, cold beer close by. You’d bet confidently on the snow which will soon fall (not thickly, but snow is snow).

“Honestly, you get used to it,” laughs Earl as we go inside and I head for the fire.

“You get to be street numb. When it comes to this sort of weather you’ve got to adapt.”

Earl calls himself ’45 years young’ but for many of them he was homeless — and there were times (he has a photo to prove it) when he looked maybe not older but gaunt and careworn.

And in case you’re wondering, Earl is his real name — although he says a good friend bought him a title recently, a novelty lordship of the manor which supposedly bestows rights to a tiny plot of land.

“So you’ll always have somewhere to sleep,” she’d explained.

It’s a good joke and Earl laughs heartily — as he often does.

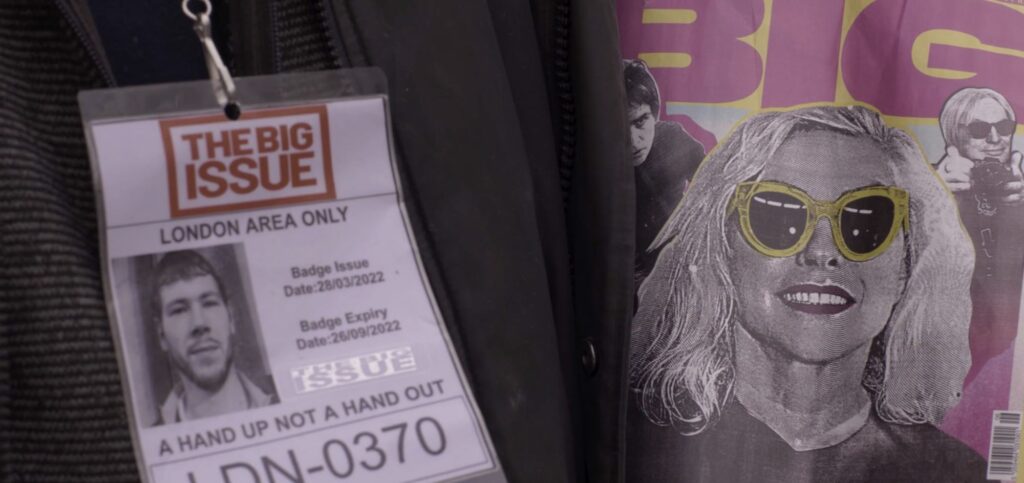

His cheeriness must have helped a lot when he was selling The Big Issue and perhaps explains why he appeared in the magazine so frequently.

“There are multiple stories they’ve done on me from when I was still an addict in London,” he tells me.

“They see me as one of the successes. And I’m a gobshite.

“I was the first vendor in the North East to have a contactless card reader. I changed people’s perceptions.”

Earl’s one of the ‘stars’ of Someone’s Daughter, Someone’s Son, a moving documentary about homelessness being premiered in Newcastle.

Made by Dartmouth Films and released following a successful Kickstarter campaign launched at The Exchange in North Shields, it boasts a voiceover by Oscar-winning actor Colin Firth.

The film focuses on individuals, putting human faces on a problem that blights Britain and challenging the idea it’s insoluble.

On screen you’ll see the cheery pub Earl. But occasionally you’ll see the face crumple. Being homeless is demeaning, debilitating and dangerous.

“It’s taken me a couple of times to sit through the film,” says Earl.

“Everything’s still raw, especially when you see it’s still going on. I was looking at some photographs of the Victorian days with people at soup kitchens. You see similar today.”

There are enough stories to show no-one’s immune and Earl’s is one of them, spilled for me in a jumble of memories and half memories.

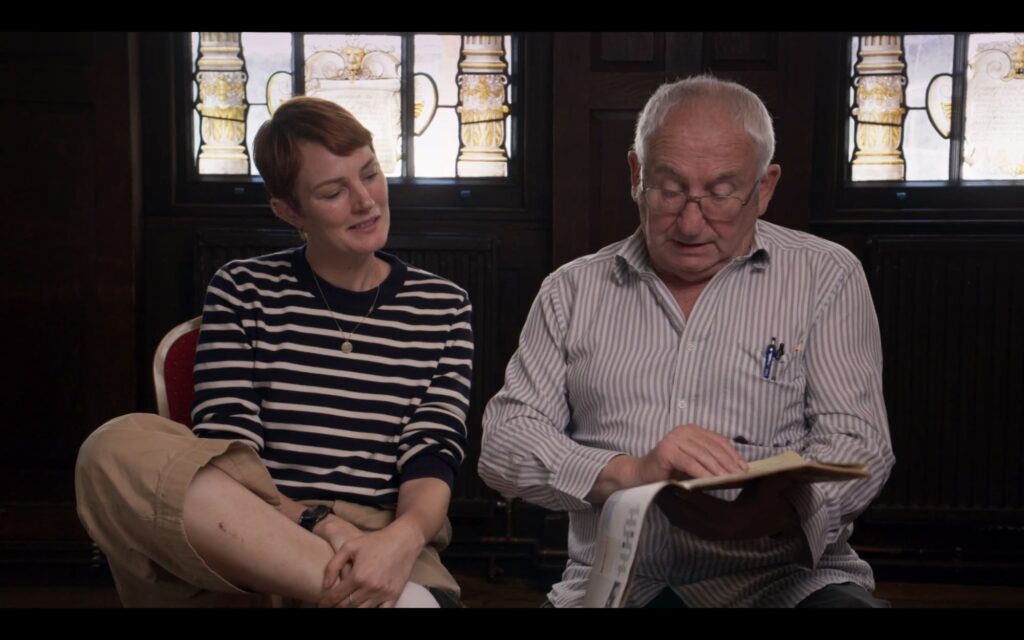

It’s a thread running through the film directed by Lorna Tucker, an up-and-coming name in the film world who was once herself on the streets.

The same streets as Earl, in fact.

They were put in touch through The Big Issue, which looms large in the film along with its charismatic founder, John Bird, one-time homeless orphan of the London slums.

“You get to be street numb. When it comes to this sort of weather you’ve got to adapt.”

Earl John Charlton

And he really does have a title.

Made a life peer in 2015, Baron Bird of Notting Hill speaks on behalf of the homeless as a House of Lords crossbencher.

Lorna and Earl found they’d been down and out at the same time and on the same cold pavements.

“When I was on Dean Street, Soho, Lorna was at the back of St Anne’s Church — she was only 14. We were doing the same thing and probably scoring off the same people but never met.

“In the first few minutes of the first Zoom call in 2019, it was like ‘Wow! I was there’.”

The way Lorna’s got her life back on track is remarkable.

Only towards the end of the film does she appear on screen, as if the emotion has finally got the better of her.

Well-spoken and with good looks unblemished, she confounds the stereotype of the rough sleeper, as do the interwoven home movie clips of the happy little girl she once was.

Neither was Earl’s fate predestined, it seems. He was born in South Shields — ‘in a good community’, he insists. There was a time when he dreamed of joining the Royal Marines.

“I was really good at school, in the juniors,” he says. “I didn’t feel I was a troublesome kid but I’d do my work quick and get bored.

“I was the class clown but I also got bullied.”

He ended up ‘racketing around’ with other lads, misbehaving.

“Me mam couldn’t handle us so I went into care at 14 years old. And do you know what? The staff were all well-intentioned lasses but back in 1991 we got criminalised before we knew what a crime was.”

At home he’d seen his stepfather hit his mother and been hit himself.

“I never wanted me mam to be tarnished,” he says. “She wasn’t the violent one so I’m not blaming her. She was one of the strongest women in the world and I know now, as an adult, that everyone needs a bit of company.

“You’re a single mother and unfortunately you get the wrong fella.”

Earl ran not from home, he stresses, but from the care system.

But not only that.

“I didn’t want to discredit my family. My grandad was a very proud man and there was a big family all doing the right things. I felt I was the only one doing the naughty things so there was a lot of factors around me running away.”

He headed for London.

“I’d never been but I’d seen films and it was always lights and glamour and streets paved with gold.”

Arriving penniless at Tottenham Court Road tube station, he saw a kid sitting down, begging.

“I was hungry. When he got up and left, I sat down. I was shy but people gave me change and then these two lads came along who I know now were called Chris and Steve and they said, ‘That’s our pitch’. Very territorial.

“I heard their accents and they heard mine and I realised they were Geordies.

“I said, ‘I just want a bit of weed, to be honest’. I used to smoke a bit in the care home. They told me where to get it.”

The Geordies invited Earl to kip on their patch and on the second night a girl gave them tablets in a bag. One lad offered some to Earl.

“I saw him neck them so I necked all these pills. Next thing, because you get all these hallucinations and flashbacks, I woke up in Hastings in a psychiatric hospital.

“I was seen climbing scaffolding and I can remember visuals of being chased by people with swords. I don’t know how I didn’t kill myself.”

Earl admits to ‘a sort of loss of memory’ relating to this hallucinatory interlude.

Eventually he found himself back in South Shields where ‘social services put me in a B&B and left me to my own devices’.

“It wasn’t long before I left again and hitchhiked to Torquay and Bristol and Weston-super-Mare where I met the girl who had my son.”

That didn’t end well. The girl, suffering post-natal depression, left with their baby (now an adult and estranged from his dad). It set Earl on a downward spiral, to homelessness again, heroin addiction and spells in prison.

The heroin, he says, was first offered by a neighbour when he was alone and depressed. He didn’t know what it was at first but it dulled the despair.

Salvation came through The Big Issue but initially in the form of a good Samaritan outside Farringdon tube station where Earl had a begging pitch.

“It was a gentleman called John Morris, a businessman who could see something in me that I couldn’t see. He never judged me and I could be honest with him.

“He knew I was an alcoholic. He bought me drink the first day but he normally bought me food. He passed every day and I always said, ‘Thank you, John’.

“One day he said, ‘Earl, don’t thank me. I’m thanking you’. He was a former alcoholic who’d got caught drunk driving and could have lost everything.

“When he learned my story we had a connection.”

Earl started selling The Big Issue and weaned himself off heroin and eventually off the methadone prescribed to help addicts manage their dependency.

He returned to the North East and when selling The Big Issue near Newcastle Central Station took it on himself to offer informal counselling, showing vulnerable youngsters the photo of himself from 2014 when he was at a low ebb.

“Me showing transparency helps them,” he says.

Eventually he got a job with the charity North East Homeless, based in North Shields.

He enjoyed the work and it was a blow when it closed in 2022, with the Charity Commission initiating an inquiry.

The film shows Earl working in the charity’s café and reports its demise with the closing credits. It’s a sad note on which to end.

Earl, though, seems to have turned his life round with a home and a new job as a YMCA support worker in North Tyneside.

Like the charities Shelter* and Crisis, he hopes the film will spur moves to tackle homelessness and drug abuse (methadone, in Earl’s view, simply panders to addiction).

Clean now and fit, he says: “I’m in a position I thought I’d never be in.”

He’s read that life expectancy for a male rough sleeper with an addiction falls shy of 40 and has lost enough friends to believe it’s true.

They include the London Geordies, both now dead, one from an overdose and the other from suicide.

“I got out in time and I’m very lucky to be here,” he says.

Someone’s Daughter, Someone’s Son has three screenings at the Tyneside Cinema on February 8. All are sold out but it’s being shown in other cities and an eventual TV release seems probable.

* Research by Shelter published in December showed homelessness in the UK had risen 14% in a year with more than 3,000 people (up 26%) sleeping rough on any given night.

Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens was the first municipally funded museum in the country outside London. It houses a comprehensive collection of the locally produced Lustreware pottery.