When so much about nature and the environment seems depressing, it’s nice to be able to report on something positive — something, moreover, that runs counter to a prevailing sense of helplessness.

The ‘something’ is beavers which are gradually being reintroduced to enclosed pockets of land across England with almost instantly beneficial effect, creating wetlands where all sorts of wildlife species thrive.

‘Ecosystem engineers’ the experts call them but the beavers don’t know that.

They’re just doing what beavers do — chewing down trees to build dams in order to raise the water level enough for them to feel safe as they move around.

Beavers are goofy looking rodents, the second largest in the world after capybaras, with fat tails, webbed back feet and immensely strong teeth.

But most people don’t seem to know much about them.

- Read more: Orchestral manoeuvres in the North

- Read more: The Globe Gallery’s story comes full circle

I didn’t know much about them myself until I joined other media folk for a daytime beaver safari at Wallington, the National Trust property that most people think of as a country house but is actually a huge estate of more than 5,000 hectares and with 15 tenant farms.

Before we head off to one of its more remote corners, a beaver briefing by Paul Hewitt, countryside manager at Wallington, and Heather Devey, founder of Newcastle-based Wild Intrigue, which has been running the beaver enclosure safaris at Wallington on the National Trust’s behalf.

Both are on a mission to educate and if Paul is a beaver convert, Heather is a longstanding fan whose deep reserves of patience have been tested on many occasions.

“CS Lewis has us think otherwise but beavers are herbivores,” she stresses.

“Write that down.”

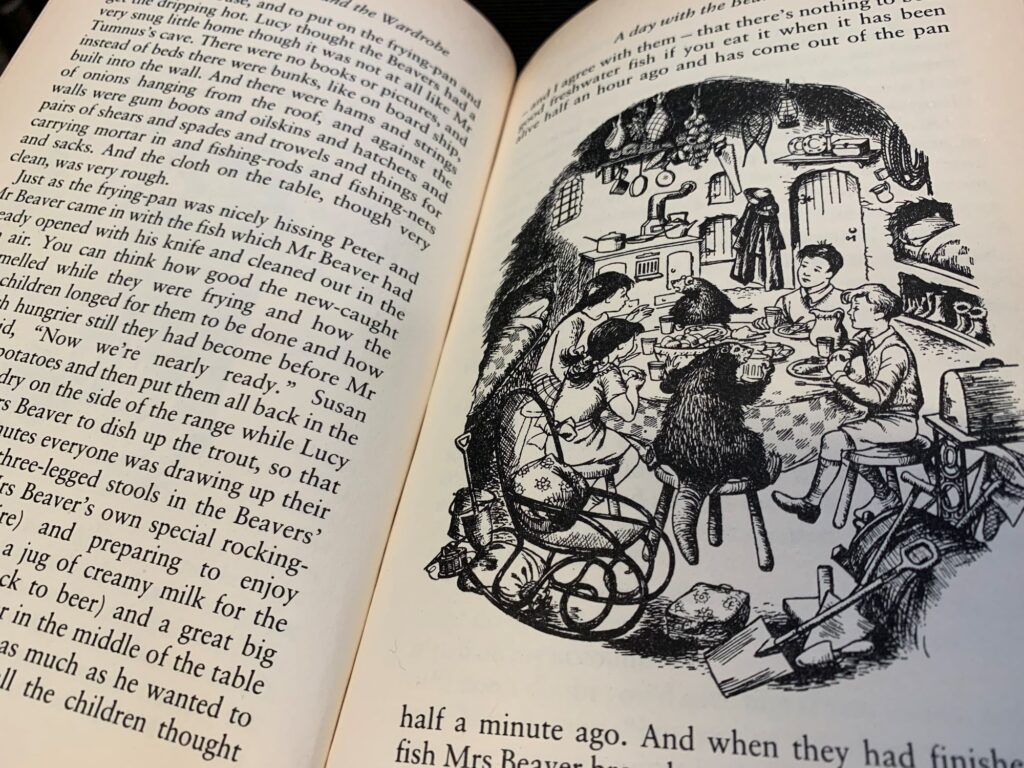

In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, with which a lot of sceptical anglers seem well acquainted, the creator of Narnia has Mr Beaver shoot his paw through a hole in the ice and fish out a beautiful trout which Mrs Beaver cooks and serves with potatoes.

“There are so many misconceptions,” sighs Heather.

“When I was community consultant on the Wild Ennerdale project in West Cumbria there was actually a town hall meeting about how beavers were a threat to children. You’re fighting against that.”

For the record, there is no evidence that a beaver has ever eaten a child… or even a fish.

Willow, on the other hand, is a beaver delicacy, as is aspen; and meadowsweet is a special favourite, especially with the young, known as kits. “It’s really soft and flavoursome for them,” says Heather, quite making my mouth water.

Young beavers can fall prey to otters and they were wiped out by humans who hunted them for their fur, meat and castoreum, a secretion used in medicine, perfumery and as a food flavouring.

Eurasian beavers are now a protected species in the UK as they make their gradual comeback.

About 300 people have been on Wild Intrigue beaver safaris since April which suggests people are keen to become better acquainted with an animal which vanished from these shores some 400 years ago.

Heather says the vast majority of participants had rated the experience highly, pleased to see something good happening to the environment for a change.

“This is the first time in northern England that people can actually come into a beaver wetland so it’s incredible that the National Trust have done this. There are a few enclosures in Cumbria and North Yorkshire but this is the only one people can visit.”

Paul Hewitt was present a year ago when a family of four beavers from Tayside — two adults, a kit and a juvenile — were released into the enclosure beside the Donkinrigg Burn.

“I’ve been working in nature conservation for 30 years,” he tells us.

Five years ago, he says, he might have asked himself: “What the hell do we want beavers for?” But this year was “amazing”, despite problematic weather.

“If there’s one really good thing I’ve done in my career, it’s bringing back beavers to Northumberland.”

Having moved from the Donkinrigg to the adjoining Delf Burn, the Wallington beavers quickly got busy, converting the traditional trickle into a network of pools through which water slowly meanders.

“What shocked me was that within 19 days they’d started building a dam,” says Paul.

“It got bigger and then they started building others. It’s amazing how industrious they are. By September they’d basically constructed four dams with water being held back 300 metres beyond this main dam to a depth of five feet.

“It never stopped raining during July and the main horror was Storm Babet when a huge torrent of water came rushing down.

“It highlighted why we need beavers. We need to try and stop this flash flooding.

“With Babet the water level went up from 30 centimetres to about a metre and a half in an hour. Most of the dams got washed out so we did intervene, putting posts in front of one of them to hold it.

“It was a shame because it makes it look a bit unnatural. But the kit survived and they’ve got fat tails which means they’re OK. They carry fat in their tails. Monitoring wise, we’ve got about 20 cameras to make sure they’re looking well.”

Even with that, though, our hosts can’t put hand on heart and swear that the four beavers — five since the recent birth of the first Northumbrian kit — are all still in the Wallington enclosure.

“They’re wild animals,” points out Heather. “They’re not meant to be in enclosures.” In Scotland they live freely. In England a licence is required before release into an enclosure whose fences must be inspected regularly.

It’s fraught with difficulty. Paul says badgers promptly tunnelled beneath one new bit of enclosure fencing. A camera caught a beaver crossing the hole apparently without noticing it.

“A beaver’s been spotted in the River Wansbeck but we’re not sure if it was one of ours. One also appeared in a canal in Wolverhampton.”

Clearly there are beavers about. Paul says Scotland’s free-living specimens probably escaped from a wildlife safari park originally, as did a population in Kent. Meanwhile a pair appeared on National Trust land at Studland in Dorset, apparently released unofficially by people wanting to force the issue.

“It’s not really helpful to the cause because it gets people’s backs up,” says Paul.

Walking single file towards ‘beaver central’, along the enclosure fence and through grass grown long because sheep have been banished, Paul and Heather show how the beavers have already changed the landscape.

Discarded twigs of foraged willow have taken root in the mud along the banks of the burn.

“This is what you get with beaver habitat,” explains Heather. “People often think they’ll decimate vegetation but you get more. This is what it looks like, wetter and greener.”

We see the dams and the stick-built lodge, where the beavers sleep, and the grazed beaver ‘lawns’ where wild flowers have grown. In the pools fish can be seen jumping and Heather tells us frogspawn, herons, kingfishers and even an osprey have been seen.

Two smallish oak trees will be left to their watery fate, probably becoming home to woodpeckers and bats before subsiding to become a deadwood habitat and further slow the flow.

Paul says the tenant who farms the land incorporating the beaver enclosure is being paid to store water for reasons of flood mitigation and biodiversity. The beavers can help with that.

“We’ve got 50 kilometres of burns on Wallington and the beavers act like a sponge, holding water in the winter and releasing it through the summer, and also cleaning it because the sediment filters out as it flows down.”

Heather says our landscape evolved for over 35 million years with beavers in it and we lived alongside them. Over the past 400 years their absence has been felt, and perhaps never more keenly than today.

The one thing we don’t see on our beaver safari is a beaver. They prefer to go about their eco-engineering under cover of darkness so a twilight safari might have been better for a sighting.

But the changed and ever-changing habitat of the Wallington beavers, covering at present an area equivalent to half a football pitch, is well worth seeing. And it raises the question: what if swathes of rural England were given over to beavers?

It’s something people are campaigning for. It seems the ball’s in the Government’s court.

You can find out more about the beavers on the National Trust’s Wallington website.